show/hide words to know

Basilar membrane: the membrane in the cochlea that is tuned to certain frequencies, or pitches. Different locations on the basilar membrane respond to different pitches.

Looking Inside the Ear

You hold a mirror up next to your ear, grab on to your ear lobe, and start bending. You tilt your head, lift your chin, and strain your eyes looking over to the side, but you still can't see inside of your ear. What if you could look, or even go, inside someone else's ear? Then you could get a really good look at all the parts that make it work. Let's all take an imaginary trip through the ear to learn about what you'd see if you could fit inside.

The Outer Ear

The large external part of your ear is called the pinna. To the right, lower part of the ear in this image is a dark area which leads to the ear canal. Image by Elmar Ersch.

Our trip starts on the outside of the ear, at the pinna. The pinna is the big part of your ear attached to your head. If you reach up and touch your ear, you are actually touching the pinna.

From the pinna, you enter a large tunnel. From here, you can still see the outside world. You are just starting your trip into the ear canal. Sound travels through this path when it first reaches your head.

As you walk through the tunnel of the ear canal, you see some yellow sticky stuff on the walls. This is just earwax. The wax is the cleaning system for your ear. It blocks dirt and debris from getting to the important parts of your ear. The earwax does this all by itself, but can only do its job if it's left in place. This is why you are not supposed to take the earwax out of your ear. If you try to clean out your own ear, it can push the wax too deep where it can’t escape and you could stop the wax from doing its job.

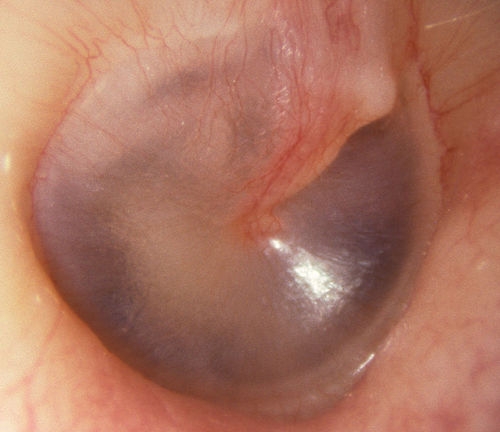

If you keep walking down the ear canal, you would take a turn and then see a large round wall. This is your eardrum, or tympanic membrane. The eardrum is a lot like the top of a drum that musicians use in a band. The eardrum is made up of three layers that are stretched across the end of the ear canal. When sound hits the eardrum, it causes a vibration that moves the layers of skin.

The Middle Ear

Now imagine you somehow made it to the other side of the eardrum without injuring the ear. You will be inside the middle ear. If you look up, you would see something that looks like a hammer attached to the eardrum. This is the malleus, the first bone in your middle ear. It is attached to the eardrum, and moves whenever it moves.

You will see another bone attached to the malleus. The incus is the next bone and works just like a lever. It helps turn the tiny vibrations of sound into movements big enough for your ear to hear.

Next in the line of bones is the stapes. The stapes looks like a stirrup for riding horses or like an old style iron for ironing clothes. The end of the stapes is attached to your cochlea by the oval window.

After walking through the middle ear, you will see the stapes attached to a very large bone. The attachment is at the oval window. The oval window is the entrance to the cochlea. When the oval window is pushed back and forth by the stapes, the fluid inside the cochlea moves back and forth.

The Inner Ear

If you go to the other side of the oval window, you would be in the cochlea. This is part of the inner ear. From the outside, the cochlea looks like a snail shell with two and a half turns. Inside the cochlea, you are in a big sphere surrounded by fluid, membranes, and cells. When the fluid is pushed by the sound, it presses down on one of those membranes, called the basilar membrane. Different parts of the basilar membrane respond to different frequencies, or pitches.

A sound with a high pitch will move the basilar membrane at the beginning of the cochlea. A sound with a low pitch will move the basilar membrane at the end of cochlea. When the basilar membrane moves, it puts pressure on tiny cells inside your cochlea called hair cells. They are called hair cells because they actually look like little hairs. When these hair cells are pressed hard enough, they fire a signal to the nerve to say that it heard the sound. The hearing nerve then carries the signal to the brainstem.

The brainstem takes the signals from the different sounds and analyzes them. Then, the brainstem sends the signals to the auditory cortex in your brain. You won’t even know you hear the sound until it reaches your auditory cortex. Once your auditory cortex gets that signal, you know that you heard the sound and you can figure out what it means, where it is coming from, and what to do next.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Eardrum image by Michael Hawke MD.

View Citation

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Looking Inside the Ear

- Author(s): Emily Venskytis

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: February 2, 2016

- Date accessed: November 28, 2024

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/looking-inside-ear

APA Style

Emily Venskytis. (2016, February 02). Looking Inside the Ear. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved November 28, 2024 from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/looking-inside-ear

Chicago Manual of Style

Emily Venskytis. "Looking Inside the Ear". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 02 February, 2016. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/looking-inside-ear

Emily Venskytis. "Looking Inside the Ear". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 02 Feb 2016. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. 28 Nov 2024. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/looking-inside-ear

MLA 2017 Style

Once sound passes through the eardrum (also called the tympanic membrane), it still has many changes to go through before the information in that sound is sent to the brain.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.