Xs and Ys: How Our Sex Is Decided

Illustrated by: Sabine Deviche

show/hide words to know

Baking cookies takes a lot more than just flour in a bowl. Image by Veganbaking.net via Wikimedia Commons.

Sarah is turning seven years old today, and she’s especially excited about this birthday. She’s going to make a bunch of cookies with her parents to celebrate, and Sarah LOVES cookies. She bolts out of bed in the morning and rushes downstairs, shouting for her parents join her. They come down to see that Sarah emptied the entire bag of flour into a mixing bowl and is stirring it happily.

Laughing, they ask, “Sarah, what are you doing?”

“Making cookies!”

Her parents smile, “Throwing flour in a bowl won’t get you cookies. You have to follow a recipe.”

“What’s a recipe?”

“A recipe tells you how to make a certain kind of cookie. It says what ingredients to use, how much of them you put in, and in what order. It has all the instructions you need to follow to make the cookies.”

Kind of like cookies, humans have instructions, too, but ours are written in our DNA. Our chromosomes are kind of like recipes that carry those instructions. Two of our chromosomes are called sex chromosomes. The DNA in our sex chromosomes has instructions that decide our biological sex.

What's In the Recipe?

DNA decides the sex of humans, in the same way that ingredients decide what type of cookie you make. Image by Jonathunder.

Sarah’s mom writes down her favorite sugar cookie recipe for Sarah to use. Sarah’s dad writes down a lemon cookie recipe. Depending on which recipe Sarah uses, her cookies will either be sugar cookies or lemon cookies.

In the same way, the instructions that are in our sex chromosomes will decide our biological sex. Humans have two kinds of sex chromosomes, an X and a Y. The mix of chromosomes you have plays a big part in determining how you will develop. People usually have two sex chromosomes. Typically, embryos with one X and one Y chromosome develop into males. And those with two X chromosomes usually become females.

We get one sex chromosome from our fathers, carried by sperm, and one from our mothers, carried by the egg. The sperm and egg fuse during fertilization, which creates a zygote that can develop into a human.

Expect X, But Why Y?

The X chromosome is larger than Y because it carries more instructions. The X chromosome has some instructions to make body parts that all people have, and others for body parts that only females have.

The Y chromosome is short, and mostly has instructions needed for typical males. It has one specific part called the sex-determining region Y, or SRY. The SRY carries some essential instructions for males, such as how to make testes. Testes are male reproductive organs. Their formation is the first step in male development.

The SRY is like the most important step in a specific recipe. In Sarah’s recipe for lemon cookies, the most important step is adding the lemon to the cookie dough. That’s what makes the cookie lemon flavored. Without it, the cookie will look and taste like a sugar cookie. The SRY is important to an embryo the way lemon is important to the lemon cookies. Without an SRY, an embryo will develop as a female instead of as a male whether it has a Y chromosome or not.

Beyond the Binary

There are more than just two possible sexes for which the chromosomes can carry instructions. While most people are typical XY males or XX females, many people are intersex. Intersex people are born with both masculine and feminine body parts. Every intersex person is different, and the body parts they might have vary. Just like there is no right way to be a boy or girl, there is no right way to be intersex.

Intersex people are neither male nor female. As intersex people get older, they may choose to identify as male or female. They can also identify as neither one if they choose.

Counting Chromosomes

The X chromosome was first named during a study of firebugs in Germany. Image by hedera.baltica via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1890, the biologist Hermann Henking was hard at work studying chromosomes in Germany. Henking stained cells he had collected from the sperm of a firebug. In those stained cells he noticed some darker spots that would later be known as chromosomes.

But there was something odd about the numbers of those dark spots that he saw in different sperm cells. Some of the sperm cells had twelve chromosomes, but others had only had eleven. He named the extra chromosome he kept noticing “X”. Sound familiar? It might, because we now commonly know the X chromosome to be one of the two sex chromosomes.

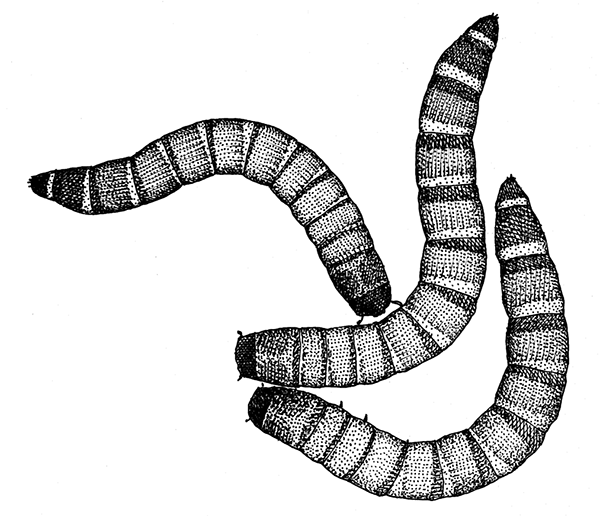

However, scientists did not find the Y chromosome until later. In 1905, the geneticist Nettie Maria Stevens was studying the cells of mealworms in Pennsylvania. She noticed that the female cells usually had twenty large chromosomes. Stevens also noticed that the male cells had twenty chromosomes—nineteen large ones and one small one.

Why do you think the males had one chromosome that was smaller than the rest?

In 1905, Nettie Maria Stevens discovered the Y chromosome while she was studying mealworm genes. Image courtesy of the Carnegie Institution of Washington via Wikimedia Commons.

Stevens guessed that the small chromosome she saw in male cells paired up with what Henking named the X chromosome. She also guessed that the small chromosome would decide if the mealworm would develop as a male or female, and she was right! She named this smaller sex chromosome Y, because Y is the next letter in the alphabet after X.

After both sex chromosomes were discovered, it took many more scientists and many more years to figure out how they work. Even today, we are still figuring out so much about our sex chromosomes and the many ways they can affect who we become.

This Embryo Tale was edited by Dina Ziganshina and Emily Santora and it is based on the following Embryo Project articles:

Haskett, Dorothy R., "The Y Chromosome in Animals". Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2015-05-28). ISSN: 1940-5030 https://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/8323.

Cox, Troy, “Sex-determining Region Y in Mammals”. Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2013-12-31). ISSN: 1940-5030 https://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/6887.

Cox, Troy, “Genetic Evidence Equating SRY and the Testis-Determining Factor” (1990), by Phillippe Berta et al.”. Embryo Project Encylopedia (2014-01-10). ISSN: 1940-5030 https://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/7357.

Cox, Troy, “Male Development of Chromosomally Female Mice Transgenic for Sry gene” (1991), by Peter Koopman, et al.”. Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2014-01-28). ISSN: 1940-5030 https://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/7515.

Three mealworms drawing by Des Helmore / Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research via Wikimedia Commons.

View Citation

Many different animal species have been involved in studies of sex chromosomes. Mealworms, which have 20 chromosomes, were important to the discovery of the Y chromosome.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.