Illustrated by: Sabine Deviche

show/hide words to know

Imagine the desert, and a bare landscape punctuated here and there by cacti pops into mind. Little water, sweaty, hot summer days and frigid winter nights make the desert an uninviting place for most animals and plants. But hiding just below the surface, the desert is alive with microbes—tiny, living things too small to see without magnification.

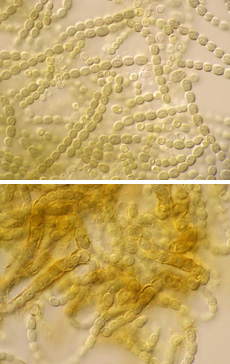

Soil crust showing teeny strands of microbes holding sand grains together.

Many different types of microbes live in the Sonoran desert, according to microbiologist professor Ferran Garcia-Pichel, who studies the minuscule inhabitants surviving in the inhospitable desert. He and the other research scientists in his lab have discovered that most of these desert residents are thread shaped and absolutely teeny—if you were to braid 10-20 of them together, they would only be as thick as a single strand of human hair.

After sifting through many different batches of desert soil, professor Garcia-Pichel has discovered that the most abundant microbe in the Sonoran desert is a blue-green bacterium called Microcoleus. While the desert is dry, these little guys dig themselves a couple of sand-grains deep below the surface. To survive in the hostile desert environment, Microcoleus desiccates, which means it dries out and shrinks until it contains only 1-2% water. Dried out, it sits and waits. “It’s very good at doing nothing,” soil scientist professor Ferran Garcia-Pichel explained. It doesn't go bad when dry, “like salami”, it just sits there in suspended animation.

Microbes producing brown 'sunscreen' pigment (bottom image) in reaction to ultraviolet light.

Nature's Sunscreen

Why would a scientist dedicate so many hours to understanding how desert dwellers survive? Professor Garcia-Pichel and cyanobacteria have a long shared history. Almost thirty years ago, Garcia-Pichel was puttering along the winding Baja coastline on his way to a NASA research station, where he was supposed to be studying how microbes formed dense sea mats. “I was about halfway down, driving along this beautiful desert when I found these strange black films or spots on granite boulders,” he said. “They were all on the north side. They were so dark, they were just black.” Fascinated by the black growths, Garcia-Pichel pulled over the car, hopped out and collected some samples.

It turned out the cyanobacteria colonizing the granite boulders produced a special golden-brown compound called scytonemin that functions much like sunscreen. The dark color protects the cyanobacteria from the damaging UV light of the sun.

Surviving the Desert Heat

Living in the desert is a tough life. The only way to survive is to shut down for long periods of time, a form a bacterial hibernation. Then quickly spring back into action when the rains arrive, Garcia-Pichel said. Even when cyanobacteria are inactive and have shut down all their active defense mechanisms, they’re still bombarded by harmful UV light. As they can’t actively repair their DNA or hunt for free radicals, they’ve invested a lot of energy in producing a thick layer of these protective pigments that act like a sunscreen.

Flipping over a single piece of drying soil crust reveals the green microbes growing underneath.

Thinking he may have stumbled across something new, Garcia-Pichel did a search of the scientific literature to see if any other scientists had encountered this special pigment before. To his dismay, Swiss scientists had described it back in the 1800s, but little research had been done since. And so Garcia-Pichel was hooked, fascinated by how such tiny living things could survive in such a hostile and desolate environment.

So while his research subjects veg out and do nothing, professor Garcia-Pichel keeps busy in his laboratory, studying what makes these hardy critters tick. Many bacteria, plants and fungi reproduce through spores that lie dormant for a long time until the conditions are right and then germinate, creating a new copy from the spore. Spores are a fantastic solution for surviving a drought or a long winter. However, in a desert, water evaporates and drains quickly, leaving no time for spore germination. It’s just too slow.

Did you know the human body can be made of as much as 80% water?

Microcoleus had to find a different solution. Moisture doesn't last in the desert, which means the microbes have no time to waste. As soon as the rains come, these thread-like cyanobacteria instantly soak up the water and spring back to life.

Most living things, including us, are full of water. Although we feel pretty solid, our bodies are made up of as much as 80% water, making us incredibly sloshy creatures. If you tried to dry us or other living things down to 1-2% water, we wouldn't come back to life when you rehydrated us.

But these microbes don’t mind. Once the rains come, they instantly bounce back into action, migrating to the soil surface and turning it green. Their bodies intertwine, weaving a mesh of fine filaments that holds down the soil. By threading their way through the soil, they hold the surface together, creating a biological desert crust. Crusted surfaces can then resist hurricane-force winds without letting the soil blow into the air.

The Fragile Side of the Toughest Desert Dweller

Invisible to us except when wet, these little guys are tough codgers. After the nuclear bomb tests in the deserts of Nevada in the 1950s, they examined the surrounding area for signs of life. Microcoleus proved to be the toughest desert inhabitant, found living closest to the bomb explosion site. Although super hardy in extreme climates, surviving near boiling temperatures or being frozen, they have an Achilles heel, a single weak spot.

Microbes in desert soil are tough, but can be harmed by soil compression.

The one thing that hurts them is when their soil is compressed. Cattle trampling over the desert, farming desert soils, racing off-road vehicles through the desert and development of desert lands—all these activities compress the soil and destroy the microbial inhabitants living there. As soon as the soil is compacted, these microbes reveal their wimpy side, dying out quickly.

Sadly it takes a long time for the soils to recover and microbes to reinhabit the compressed soil. In many places the microbes have disappeared. In the nature reserves of Oregon, where the western way of life with cattle ranching continues to this day, intact soil crusts are hard to find. The microbes only exist in areas fenced off from cattle or under bushes.

Native Americans have learned to live in the desert. They walk in their paths, instead of trampling everywhere. Such simple behaviors allow the microbes to flourish, so they can weave the soil into a desert crust. When the desert crusts disappear, nothing else is there to hold the soil down. Without these soil microbes, the desert surface is prone to erosion, resulting in more blowing sand and dust storms.

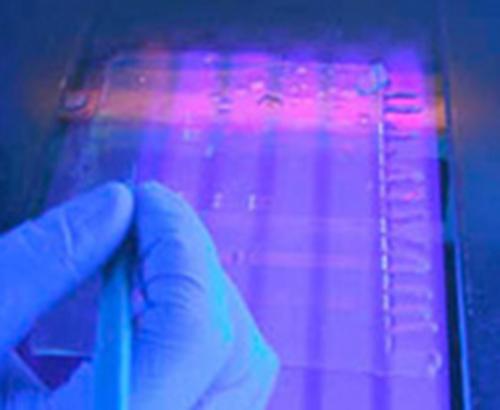

To help regenerate soil crusts in damaged areas, scientist professor Garcia-Pichel has been learning more about these microscopic desert inhabitants using some nifty CSI techniques. Learn more about how he tracks down these invisible microbes in Tracking the Invisible.

This section of Ask A Biologist was funded by NSF Grant Award number 020671.

References:

Additional Images from Wikimedia(link is external).

View Citation

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is one of many techniques used to uncover clues about desert microbes.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.