show/hide words to know

The Sense of Touch

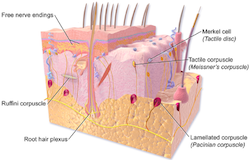

The skin contains receptors that enable a person or animal to feel touch. Image by Agustín Ruiz.

The wind howls outside as the rain pounds against the window. With a sudden flash of lightning, the lights in your room go out. Vision won’t help very much in the darkness of the room, but you know there is a flashlight in the nightstand next to the bed. You move your hands toward it, find the drawer handle, and open it. You start to feel around for the flashlight.

As you touch each object in the drawer you can identify it immediately. After a few tries you feel the rubber grooves of the flashlight handle. With a sigh of relief you pull it out of the drawer and turn it on. While you may think you have psychic powers to be able to correctly identify the flashlight from the other items you touched, your skin did most of the work.

Skin has many types of receptors that help you feel the things that you touch. In your body, a receptor is a structure that can get information from the environment. The information is then changed into a signal that can be understood by the nervous system. Receptors that let the body sense touch are located in the top layers of the skin - the dermis and epidermis.

Receptors are small in size, but they collect very accurate information when touched. They may sense pain, temperature, pressure, friction, or stretch. Unique receptors respond to each kind of information. This helps provide the body with a full picture of what is touching the skin.

- Thermoreceptors (thermo = heat) sense temperature. They do this by changing their level of activity. For example, if the temperature becomes colder, thermoreceptors that sense cold will be more active. The ones that sense heat will be less active.

- Nociceptors (noci = to harm | ceptor = receptor) sense pain, but maybe not pain in the way a person normally thinks about it. We think of different types of pain related to a cut or a burn, but nociceptors can't tell one from the other. They only detect damage to skin cells. So while a person might think about pain as being different for a burn versus a cut, nociceptors get similar information in both cases.

- Mechanoreceptors (mechano = machine) sense contact with the skin. These receptors are mechanical, which means they feel physical change. The change could be when an object presses firmly or just brushes against the skin.

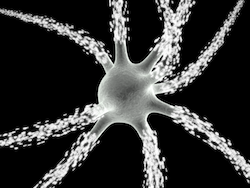

Touch receptors are neurons. They send information about touch to the brain through action potentials. Image by Nicolas P. Rougher.

While each of these sensory receptors responds to a specific type of touch, they all act in the same way when they are activated. As part of the nervous system, these receptors will fire an action potential. Action potentials are signals sent by the special cells, called neurons, that make up the nervous system. They are used to share many different kinds of information within the nervous system. Action potentials from all of these receptors will send signals to both the spinal cord and the brain.

Neuroscientists still aren't sure how signals from these receptors are changed into information that a person can understand. For example, when you are tickled versus poked, you know right away what happened. But how does the brain let you know whether it's a tickle or a poke based on only a few action potentials? Scientists continue to study this question.

Image of hand touching water by Agustín Ruiz.

View Citation

Our sense of touch helps us to interact with the world around us. Learn more about the brain and what regions process touch in A Nervous Journey.

Learn more about our five senses.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.