Sugary Surprises from RNA

show/hide words to know

What's in the Story?

If you breathe in deeply right now, you will inhale some dust, some pollen, and probably a good dose of microbes. Microbes live everywhere…on the ground, on your body, and, yes, in the air you breathe. Because we are always surrounded by microbes, our immune systems have ways to protect us from the ones that can make us sick. Just like we need energy from food for our body to work properly, our immune cells also need fuel to work and defend us.

The world around us is full of microbes. Our immune systems are always working to protect us against potentially harmful invaders.

All of the work that goes on in the body is carried out by DNA. Genes in DNA hold the instructions to make RNA, which are special messengers in the body. Most RNAs instruct the body to make important molecules called proteins. The genes that are a part of this process are called protein-coding genes.

But some genes make special RNA molecules that don’t have the instructions to make proteins. Instead, they might have different instructions that can, for example, help immune cells get nutrients. In the PLOS Pathogens article “Immune-inducible non-coding RNA molecule lincRNA-IBIN connects immunity and metabolism in (link is external)Drosophila melanogaster(link is external),” scientists used flies to study how this special RNA might help immune cells get the energy that they need to be good defenders.

It's All in the Genes

In an army, the Captain shouts instructions, and her soldiers line up, ready for orders. Once they get their orders, the soldiers carry out their jobs. Parts of our cells work in a similar way. The DNA in a cell is like the Captain, giving instructions to its soldiers, the RNA molecules. Some RNA molecules bring these instructions to cell parts that make proteins. The instructions in DNA that can make proteins are called protein-coding genes. But not all RNA molecules carry instructions to make proteins. The instructions that do not lead to proteins are called non-coding genes.

The Time to Use Genes

Whether or not they are coding for proteins, there are certain times that some genes don’t need to be used. This means that our genes are not all turned on at the same time. In the same way we might control the heat in our houses by turning it off or on, cells in our body have ways to turn genes off or on. And just like we adjust the level of heat on the thermostat, cells can also control how much of each gene will be made. This process is called gene expression.

DNA codes are sent out of the nucleus in RNA molecules. Some parts of this code make proteins and so are called protein-coding genes. The parts that don't make proteins are called non-coding genes.

When you get sick, your body launches an immune response. Your immune cells need energy to fight an infection and protect you. Scientists know that many genes get turned on or off to start this fight. This includes genes that help cells get energy.

Scientists aren’t always sure of the jobs of non-coding genes, but they know some are turned on when important things happen (like during infection). In this study, scientists wanted to find out if non-coding genes are turned on to help immune cells get the energy they need to protect our bodies and, if so, how they do that

First, scientists needed to know which genes were used during an immune response, so they looked at gene expression in flies. Scientists infected flies with bacteria to make them sick, then looked to see what the immune cells did to protect them. Sick flies were compared to healthy flies to find genes that help fight off germs.

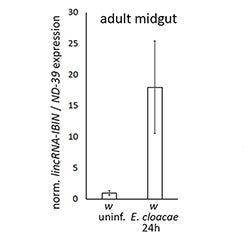

Scientists used a technique called Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR). Using qPCR, they made copies of the RNA from the immune cells, until there was enough to measure. Scientists found that a special RNA molecule was made in large amounts after infection with bacteria. The RNA did not carry instructions to make a protein. This means that it was non-coding RNA. The scientists decided to call this special RNA lincRNA-IBIN (Induced By INfection).

Location Matters

Researchers used fruit flies to test where in the body RNA production was increased, in the immune cells in the blood, or in the fat bodies? Image by Sanjay Acharya.

The scientists wanted to know what this RNA was doing to help protect the body from infection. They also wanted to know where in the body the RNA was being turned on. One place they looked was in the midgut. That’s the part of the stomach where nutrients are absorbed in fruit flies.

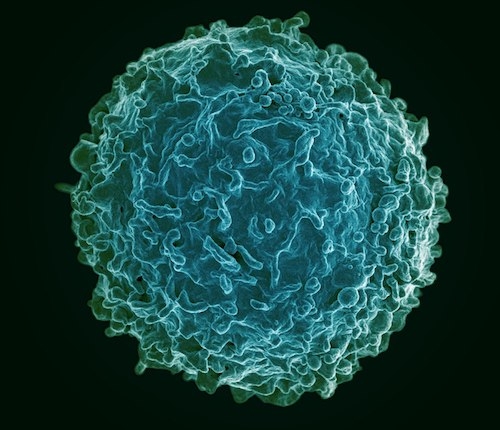

The scientists found that the RNA was made in the gut, only in sick flies. This means that lincRNA-IBIN might work with the midgut to get the nutrients needed to fight infection. Scientist also found that the RNA was made in immune cells found in blood, called hemocytes. Turning its expression up caused the number of hemocytes to grow. They also found the RNA was expressed a lot in an organ called the fat body. The fat body stores and releases energy, and makes immune molecules.

Smart Cells Feed their Troops

Scientists can control how much of a gene is made in flies. They can turn gene expression up or down in the fly, like a thermostat. They used this ability to test their next question. Scientists wanted to know what happens if the special RNA was turned down in an infected fly or turned up in a healthy fly. To see how gene expression changes when lincRNA-IBIN was turned up or turned down, they turned it up in some flies, but not others. Then, they compared gene expression between them.

They found a group of genes that flies expressed more when infected and when they had more of the special RNA. This group of genes helps break down sugars. The body needs these sugars to fight against infection. They also found that sick flies had more sugar in their blood than healthy flies. Flies also had more sugar in their blood when lincRNA-IBIN was turned up. This means that lincRNA-IBIN might help release energy when the body is fighting an infection.

Special Instructions in Long Non-coding RNAs

DNA holds information that our bodies need to work properly, but scientists are still trying to unlock its secret messages. A lot of the research from the past looks at protein-coding genes. Newer research has started to look more closely at long non-coding RNAs, like lincRNA-IBIN. Understanding how long non-coding RNAs can release sugar stores in the body may help us learn more about certain diseases. If these RNAs can be controlled, it could be a helpful tool in fighting diseases.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons and Pixabay. Human lymphocyte by NIAID. Sugar crystals by Lauri Andler.

View Citation

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.