Illustrated by: Hannah Kalas

show/hide words to know

Your immune system has a memory of its own that helps you fight off familiar germs. Image via Pixabay by Luisella Planeta Leoni.

You’re sitting at your desk, pencil ready, watching your teacher pass out today’s science quiz. Suddenly, a classmate sneezes. No matter how much information your brain has stored, it can’t protect you from the germs floating around you now. Luckily, your brain isn’t the only system in your body that can learn.

As long as your body has been exposed to these germs before, your immune system will remember them, and use its tools to kill the germs before they can harm you. Similar to when you study for a test, your immune system is able to learn the germs it meets in your body and then remember them for a later challenge.

Our immune systems are pretty amazing, but they can’t catch everything. We can help our immune systems by having healthy lifestyles and getting approved vaccines.

New Solutions to Old Problems

When COVID-19 hit, viral immunologist Douglas Lake was busy in the lab. He was studying how the immune system responds to cancer and a fungal disease called Valley Fever. He developed a way to test for Valley Fever, which is often difficult to diagnose.

Neutralizing antibodies are especially helpful against certain viruses. They attach to the virus and can block it from infecting a cell. Modified from an image from Pixabay by Mohamed Hassan.

When the virus that causes COVID-19 spread around the world, Lake immediately saw a way to help. He learned that one-third of the recovered patients still did not have the antibodies to fight the virus. Antibodies are proteins that travel through our blood, looking for problem pathogens. Most of them find and attach to viruses and bacteria in a way that destroys them directly, or marks them as a problem so other cells will attack them. However, neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) work in a special way. NAbs protect people from infection by blocking the viruses from entering our cells.

Early in the fight against COVID-19, doctors could only treat patients by giving them plasma from other patients (donors) who had recovered from the virus. Plasma is the liquid part of blood that contains antibodies, including NAbs. The idea behind this treatment was that NAbs in plasma can help sick people fight the virus by blocking infection. The problem was that some of the donor plasma from previously infected people did not actually have protective NAbs in it.

A Rapid Test for COVID-19 Antibodies

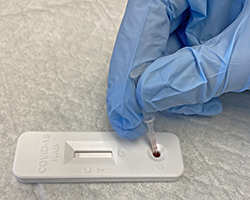

Lake realized that a test was needed to measure levels of protective NAbs in donated plasma. With this in mind, he sketched out a rapid test strip that can measure levels of NAbs in a drop of blood. The strip contains the spike protein from the virus that allows it to infect cells. It also contains the cellular receptor for the virus, which is sort of the doorway that the virus uses to enter the cell. If the drop of donor blood holds a lot of NAbs, they block the spike proteins from attaching (or “binding”) to the receptors. If the blood holds low levels of NAbs or no NAbs, the spike proteins can bind to the cellular receptors. When the spike proteins bind to the receptors, a blue line shows up on the test. A dark line means there are not many NAb’s in the blood, and no line or a light line means there are a lot. In this way, this 10-minute test lets researchers measure levels of NAbs in blood.

Lake's COVID NAb test is helping researchers understand how well COVID-19 vaccines work and how we can use them to better protect our population. Image courtesy of Tyler Quigley.

In this test’s simplicity lies its genius. Lake’s eye for problem solving led him to think of a simple solution to test plasma for NAbs. His experience with infectious diseases taught him that tests need to be cheap, fast, and accurate. Even though he invented this test to identify NAbs in plasma, it is now being used in other ways. The test can measure how well vaccines trigger the body to make NAbs and how long they last over time.

Lake’s test can tell us when our immune systems needs another vaccine dose to help protect our bodies. These tests can be used by hospitals and pharmacies to quickly test for antibodies. Armed with these tests, doctors and researchers can better decide when to give a booster vaccine. It turns out that some people need boosters sooner than others.

Studying our Invisible Neighbors

The microorganisms in and on our bodies outnumber our own cells. They are so small, we can’t see them without a microscope. Most of these “invisible” neighbors are good guys, but some are bad. Like the virus that causes COVID-19, the “bad guys” can emerge suddenly, and spread around the world. Even within our own bodies, cancerous cells can grow out of control and threaten our lives. Simply put, our world is full of tiny pathogens and misbehaving cells. We have scientists like Lake to thank for helping to protect us against the dangers we often can’t see.

Detect and Protect was created in collaboration with The Biodesign Institute at ASU.

Additional images via Pixabay. Stop COVID-19 glove picture by fernando zhiminaicela.

View Citation

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.