show/hide words to know

Did you ever wonder what causes river rocks to be slippery? Can you believe it's the same thing that causes plaque on your teeth?

The "thing" we're talking about is a biofilm, a microscopic structure formed by bacteria on a solid surface in a liquid environment.

Biofilms grow in three main areas: the natural environments like on riverbed rocks, industry like in oil and water pipelines, and a host organism including humans.

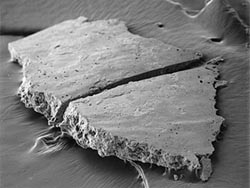

Remember to brush your teeth, or you will get a lot of this nasty looking plaque, also called tartar, stuck to them.

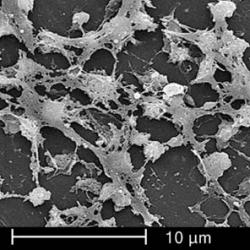

A unique process occurs inside the biofilm. When many bacteria gather, it is almost as if they communicate with each other. They send each other signals to make exopolysaccharides (EPSs). EPSs are strings or chains of sugar with the bacteria located inside. Another way to picture this is to think about fruit Jello. Imagine that the Jello is the EPS, and the pieces of fruit inside it are the bacteria.

Because EPSs protect the bacteria, the bacteria becomes resistant and hard to remove. Antibiotics, human antibodies, and other chemicals are unable to kill the bacteria, so it continues to spread. It is these resistant bacteria that cause infections in humans.

Valerie Stout, an associate professor in ASU's Department of Microbiology, has been studying the synthesis of EPS for the past 13 years. A year ago, she also began to look at biofilms.

"I'm interested in how bacteria are able to cause disease," she said. She wants to learn how bacteria can get around and outsmart the immune system. It's almost like a battle, she says, between the body's immune system and the bacteria.

"We think of bacteria as being simple organisms, but they've developed an elaborate defense system to get into the body, evade the immune system of humans and cause disease." Humans are complex, so they should be able to fight off bacteria, she said, but bacteria have evolved so that they are able to outsmart the human immune system. This is what fascinates Stout.

Taking a closer look at biofilms with an electron microscope. The sticky-looking substance between the round cocci bacteria are the biofilms. Scientists have found these films make it harder to treat and kill bacteria when using drug treatments like antibiotics.

Which bacteria are responsible for making the EPS and where are they located inside the EPS? Is it possible to give the bacteria signals to stop making EPS?

So far, Stout's experiments have shown that biofilms stick differently to different surfaces. She has also observed that biofilms stick better to a surface if they have not yet started making the EPS.

Stout is now conducting experiments involving E. coli, one type of bacteria that causes urinary tract infections in humans, often due to the use of catheters. Catheters are tubes placed inside hospital patients. The tube is inserted into the bladder and extends out of their bodies and into a bag. The wastes of immobile or unconscious people are emptied out into the bag so they don't have to get up to go to the restroom while they are still recovering from an operation or illness. Doctors put catheters into most surgical patients. Resistant bacteria inside biofilms often begin growing on the walls of the urinary tract, so that a large number of people with catheters get infections.

Stout thinks that if there was some way we could signal bacteria to stop making the EPSs, then there would be no biofilm. Without the protection of the biofilm, the bacteria would become sensitive to harmful chemicals. Thus, antibodies, antibiotics, or other chemicals would easily be able to destroy the bacteria. And this would prevent the spreading of plaque and other harmful bacteria in our bodies. Stout's long-term goal is to find a treatment for urinary tract infections.

Stout thinks that if there was some way we could signal bacteria to stop making the EPSs, then there would be no biofilm. Without the protection of the biofilm, the bacteria would become sensitive to harmful chemicals. Thus, antibodies, antibiotics, or other chemicals would easily be able to destroy the bacteria. And this would prevent the spreading of plaque and other harmful bacteria in our bodies. Stout's long-term goal is to find a treatment for urinary tract infections.

Now that you learned about biofilms, you know one good reason to brush your teeth! You can stop the plaque from becoming resistant. Prevent it from spreading throughout your mouth and damaging your teeth and gums. Something you and your dentist will both like.

View Citation

Valerie Stout's research is battling bacteria and the films they like to call home.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.