Shorter Winters and Wolf Leftovers

Illustrated by: Sabine Deviche

show/hide words to know

What's in the Story?

A grizzly bear searches for food. Image by JillWellington via Pixabay.

A hungry bear wakes up and stretches after a long hibernation. Their empty stomach growls with hunger. It sends them outside to walk around, looking for food. After a couple hours, they get lucky and find their favorite treat: leftover elk.

The elk was killed by wolves. When wolves don’t finish all of their dinner, other animals like bears eat the leftovers. Animals that feed on leftovers from a kill, or carrion, are called scavengers.

In Yellowstone National Park, most dead elk in winter are killed by wolves or snow. But now, winter is changing. As winters get shorter, fewer elk are dying from snow. Does this mean that scavengers will go hungry, or can wolves keep the carrion coming?

In the PLOS Biology article “Gray Wolves as Climate Change Buffers in Yellowstone(link is external)”, scientists studied if carrion from wolf packs is more important as winter gets shorter. Using data on wolf pack size, snow depth, and carrion availability, they created models to test this idea.

What's Happening to Winter?

Mammoth Hot Springs is near one of the sites in Yellowstone where scientists have studied weather for decades. Image by HlgeriaK via Wikipedia Commons.

In the last 100 years, the average temperature on earth increased by 0.6 degrees Celsius. This has changed weather patterns. Those weather patterns can change when the last snow of winter melts away or how high the snow cover is.

One of the places where weather has been studied for years is Yellowstone National Park. There, winter data for the last 55 years showed a clear trend. At one site, in the months of February, March, and April, there is now less snow than in past years. At another site, there was less snow than in past years during March and April. The data also showed that winter was getting shorter because there was less time with snow on the ground.

Snow, Wolves, and Elk

A little snow can make a big difference. The deeper the snow, the harder it is for elk to find food or move around. This can cause them to spend more energy than they bring in. If this happens, they may weaken, die, and then become food for scavengers. In this way, how deep the snow is can affect how many elk survive winter.

In Yellowstone National Park, a single bull elk walks through light snow.

But in warmer winters, there are fewer elk deaths from snow. This is good news for elk, but bad news for hungry scavengers like bears and bald eagles.

There is one thing that has a stronger effect on elk death than snow—wolves. Wolves are the number one reason for dead elk in winter. As wolf packs have grown since they were reintroduced in 1995, the wolves have made more carrion. The larger the wolf pack, the more food they leave behind for scavengers.

However, deep snow is still the second biggest reason for dead elk in winter. As winters get shorter and less snowy, there is less carrion from the weather. This means scavengers depend on wolves for carrion more and more. But how much of a difference do wolves really make? If there were no wolves, how much less carrion would there be?

Scientists Working Together

Scientists needed to compare a changing climate with and without wolves. But how could they do this now that wolves are always present? By using special data tools made by other scientists.

To look at the effects of winter on carrion both with and without wolves, the researchers used equations created by other scientists. The equations were built using old data, but can be run with new data to make new predictions. They ran the equation with data on wolf pack size, snow depth, and monthly carrion availability.

The snow depth data was from November to April from years 1950 and 2000. This meant there were 4 scenarios: 1950 winter with wolves, 2000 winter with wolves, 1950 winter without wolves, and 2000 winter without wolves.

Each of these scenarios were run hundreds of times with the equations. The equation only uses a few data inputs, like wolf pack size. When scientists use equations to test trends in data, or in simulated data, it is called modeling. Modeling let scientists see how total carrion had likely changed from 1950 to 2000, with or without wolves.

Do Wolves Make a Difference?

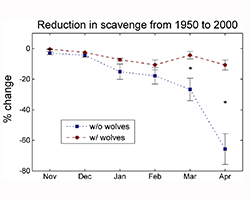

Modeling showed that Yellowstone winter months in 2000 had less total carrion than 1950. How much less depended on the wolves.

Compared to April 1950, there was 66% less carrion in April 2000 without wolves. But with wolves, there was only 11% less carrion in April 2000.

Compared to March 1950, there was only 4% less carrion in March 2000 with wolves. But without wolves, there was 27% less carrion in March 2000. In other snowy months, there was only a slight difference with or without wolves.

These results show that the total carrion is decreasing over time. As the winters grow shorter, March and April get warmer, and there is less snow. This means the amount of carrion from deep snow is decreasing. As climate change continues, the snow depth may continue to decrease even more.

Thankfully, carrion still comes from wolves. Without wolves, there would be much less leftovers for scavengers. This is especially true in later winter months, like March and April.

This confirms that even though the climate continues to change, wolves can make a difference. Thanks to wolves, maybe some bears can keep enjoying a big elk leftover dinner after hibernation.

Additional References

National Park Service, Yellowstone. "Wolf Restoration." https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/wolf-restoration.htm (link is external)

View Citation

A pack of wolves feeds on a bison in Yellowstone National Park. Wolves hunt many large animals, including elk. In Yellowstone, wolves and snow are the biggest killers of elk. As winter shortens, and snow has less of an impact on elk, are wolf kills becoming more important?

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.