show/hide words to know

Why Do We Get Sick?

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States. Why are the rates of heart disease so high? Image by Jebulon.

Cancer, heart disease, anxiety, depression, diabetes, obesity… despite the success of humans across the globe, there is a long list of diseases that affect us. Why do we still have disease, even after evolution has shaped our bodies over billions of years? Instead of asking why an individual person gets sick, this question focuses on why our bodies were shaped in ways that makes us vulnerable to disease. In the field of evolutionary medicine, there are six main kinds of reasons that help explain why we are vulnerable to getting sick.

-

Mismatch. The environments we live in today are very different from the environments in which we evolved. Environments can change quickly, but the evolution of organisms, especially those with long generation times, may lag far behind. This means that we live in conditions where the food availability is different, the exposure to pollution is higher, exposure to bacteria is lower, and our lifestyles are more sedentary than they used to be. Much chronic disease results because we are living in new conditions in which we did not evolve.

-

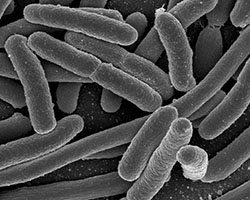

Humans have evolved alongside many bacteria, such as Escherichia coli.

Coevolution. We evolved along with many other organisms. Some of them, like bacteria, viruses, and worm parasites, have affected our evolution (just as we have affected theirs). These microorganisms evolve much faster than we do, and they quickly evolve ways to avoid most of our defenses. For instance, new antibiotics are useful for only a few years before bacteria evolve resistance. In the United States each year about 2 million people get infections resistant to antibiotics, and about 23,000 people die from such infections.

-

Trade-offs. Evolution does not occur in a vacuum. Changes in one trait that are beneficial can have resulting costs, and can be balanced by negative effects elsewhere. This is what we call a trade-off. For example, individuals with higher blood pressure may have greater exercise ability, but at the cost of damage to the tissues in later years. Another example is humans losing most of the hair (fur) that covers skin in most other primates. This enables better cooling of the body, and the ability to chase animals over long distances without overheating. There are downsides however, including increased exposure to the harmful UV rays in sunlight that can cause skin cancer. In evolution, nothing is perfect; all changes that bring benefits also have costs.

-

Constraints on natural selection. Natural selection is one mechanism by which evolution occurs. Mutation, migration and genetic drift also influence evolution. Natural selection is constrained because it can only build on what currently exists. So, once an important body part, nerve, vessel, or function has developed, it’s nearly impossible to start over from scratch. Instead, as that body plan evolves, small changes will be made on top of the original. The path of the nerve to the vocal cords provides a fine example; that starts in the brain, it goes all the way down to wrap around an artery in the chest before ascending again to the vocal cords. This long path down the neck exists even in a giraffe! This is a leftover piece of a design that started in fish, when the nerve was hooked under an artery near the heart. The giraffe shows the constraints on natural selection—remember, it acts by making small adjustments to an existing plan. That process makes it impossible to just throw away a plan and start all over again.

-

Reproductive success at a cost to health. Natural selection doesn’t work to directly increase lifelong health. Instead, it only acts on traits that affect our reproductive success. While many traits that increase reproductive success are linked to positive health (you have to live to reproduce, after all), some traits that increase reproductive success can be bad for overall health. For example, high production of the hormone testosterone helps males have more offspring, but it also increases the chances for testicular cancer and heart disease. This increased risk of disease is worth the benefit to reproductive success. Diseases that affect reproduction are heavily selected against. Diseases that don’t affect reproduction—especially diseases that generally occur after reproductive years—don’t face the same strength of selection.

-

Some defenses, like sneezing or fever, may be adaptations that help us avoid or survive illness. Image by James Gathany.

Defenses and suffering can be adaptations. Our bodies are adapted to defend against danger. We cough to remove microbes from our lungs and throats, warm up with fever to help fight against infection, and get anxious to help avoid harm. But sometimes, our defense systems can over respond. For example, excess anxiety is a very common problem. It is likely a case of misregulation of our defensive response against danger. Overall though, we must realize that cough, fever, vomiting, and diarrhea may be signs of disease, but they are likely called to action as a defensive response, rather than as a part of the disease.

So with all of these ideas, why don’t we have the causes of specific diseases all figured out? In part, because disease is very complicated. A single disease may be best understood by considering combinations of multiple explanations. For example, atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) is common mainly in modern environments, so it is a product of mismatch. However, the immune system is also involved; cells that line the arteries for defense are involved in inflammation that contributes to the disease. Also, the number of immune cells present in the arteries is governed by a trade-off between the benefits of protecting against bacteria in the arterial wall, and the costs of inflammation causing atherosclerosis.

To better prevent and treat disease, it is very helpful to understand why we are vulnerable to diseases in the first place. By approaching this question with evolution in mind, the field of evolutionary medicine can help us make new strides in understanding and improving health.

Great research in evolutionary medicine is occurring at Arizona State University’s Center for Evolution and Medicine (CEM) and at a variety of institutions across the globe. The CEM is also working on a collection of educational resources that can be found at EvMedEd.org(link is external). For new updates on the field of evolutionary medicine, visit EvMedReview.com(link is external).

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. San people image by Aino Tuominen.

View Citation

One leading theory about why many diseases are more common today is that our environment and lifestyle does not match that experienced by our human ancestors. Much of our evolutionary history was spent in hunter-gatherer societies, similar to that of the San people of South Africa.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.