Creating Chimeras

Illustrated by: Sabine Deviche

show/hide words to know

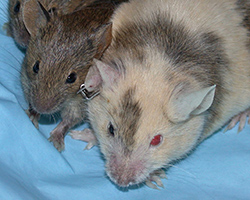

It’s 1968, and you are a researcher in charge of a group of mice. Half of the mice are black, and half are white. In this species, there is no natural mixing of fur color. So when they mate, only one color shows up in their fur. But what if you want to make both colors show up in their fur?

Beatrice Mintz found an answer to that very question. In 1968, she fused a black mouse embryo with a white mouse embryo. The offspring came out striped, and had two sets of DNA. Mintz called them “multi-mice.” Most scientists, though, call them chimeras.

What are chimeras? In Greek mythology, chimeras are mismatching monsters that have a lion’s head, serpent’s tail, and goat’s body. But in science, chimeras are organisms that possess two sets of DNA instead of one.

So why would a scientist like Mintz even want to create chimeras? Let’s delve deeper into what chimeras are to find out.

Chimeric Creation

To understand how chimerism is special, we need to look at how most organisms get their DNA.

This is what a chimera looks like in Greek mythology. It has the head of a lion, the body of a goat, wings of a falcon, and tail of a serpent. To modern scientists, "chimera" means something very different. Image by saliko via Wikimedia Commons.

All animals inherit DNA from their parents. Some of the DNA comes from the egg, and some of the DNA comes from the sperm. The egg and sperm fuse together to form a zygote with one full set of DNA. That zygote can eventually grow into an embryo, which can then grow into a fetus. All the cells in that fetus will (usually) contain that same DNA.

So, that’s how an organism gets one set of DNA. But to create an organism with two sets of DNA, two embryos must fuse together. That can happen in nature, but scientists might also fuse embryos on purpose.

Experimenting with Embryos

Before Mintz could create a chimera, she had to figure out how to fuse two embryos. But embryos initially have an outside layer called the zona pellucida. That layer protects the embryo from harm, but also makes it difficult to access it. Other scientists had tried to peel back the layer, but they had damaged the embryo in the process.

This is a mouse fetus. Like in most cases, every cell in this fetus carries the same DNA. However, in chimeras, two zygotes can fuse. Then a single fetus like this will carry two sets of DNA. Image by Ibackes via Wikimedia Commons.

How did Mintz access the embryo, then?

Mintz decided to use an enzyme called protease to dissolve the zona pellucida. Then, when she placed the two embryos next to each other, they stuck together. As neither embryo was damaged in the process, they fused, meaning the contents of their cells combined to form just one cell.

But, the two sets of DNA from each of the original cells did not combine. Instead, each set of DNA remained unchanged, but they both existed side-by-side within the new, single embryo. The embryos Mintz created in that way grew into chimeric mice that seemed normal. They just had striped colors.

Those mice were proof that we could make chimeric embryos without harming them.

Looking into the Laboratory

But why would scientists like Mintz want to create chimeras, anyway?

Some scientists do so to help learn how cells develop in the body. One example of that is Nicole Le Douarin and Charles Ordahl’s experiment in 1976. They took cells from a chicken embryo and a quail embryo, and dyed the chicken embryo cells. Then, they cut cells from each animal in half so they could fuse the quail cell halves with chicken cell halves.

The two scientists watched the different cells move around as they formed different parts of the body. That helped scientists realize which cells form which parts of the body in vertebrate animals. Le Douarin also used her experiments to track the development of the immune system. Identifying which cells grow into which structure lets us figure out which cells can help regrow a limb, or a kidney, or other parts.

Normal and Natural

Creating chimeras might sound like science fiction made real. But some chimeras already exist around us.

Have you ever stumbled across a male calico cat? Then you have seen a chimera! Male calico cats have two sets of DNA: one that codes for orange fur, and the other for black fur. As a result, they show both colors in their fur.

Spotted mice and some parrots are also natural chimeras. Still, we mostly find chimeras in labs.

Mammalian Mixes

So there have been bird chimeras and mouse chimeras. What about other animals?

In 2012, scientists created three chimeric rhesus monkeys, named Roku, Hex, and Chimero. They look male, and have mostly male sex chromosomes. But Roku also has female sex chromosomes in some of his cells, making him a chimera. Image by Vanthaso via Pixabay.

Scientists at the Oregon Health and Science University created the first chimeric monkeys in 2012. Those three monkeys, named Roku, Hex, and Chimero, each have 6 sets of DNA.

Scientists will often use mammals that are chimeras to model diseases. Some scientists use mice to model diseases like AIDS, because mice are mammals, like humans. But there are a lot of differences between mice and humans. Scientists hope that chimeric monkeys will be a better model, as monkeys are primates, just like humans.

Human Hybrids

Scientists haven’t stopped trying to make chimeras in non-human animals. But in the mid-2010s, scientists also began to make part-human chimeras. Those are organisms that have some human cells, and some cells from other species.

Why would scientists do that? One reason is to test treatments against certain diseases. Scientists need to make sure treatments are safe for humans. But they need to do this before testing them on humans. So what can they test treatments on?

Scientists study diseases and medicines using model organisms, like rats. But rats and humans are very different, so these critters are not always the best model. That's why some researchers want to make part-human chimeras. Those could be better models for testing treatments for humans. Image by Sarah Fleming via Wikimedia Commons.

Often, they test treatments on other animals. But, other animals might react differently to a treatment than a human would. That’s where a part-human chimera can come in handy. Scientists can use chimeras to test how a treatment affects human cells without having to put humans at risk. That would let scientists be more sure that a new treatment or therapy they are working on is safe to start testing on humans.

Scientists also hope that part-human chimeras can help to fill the demand for organ transplants. If there was a way to grow a human kidney in another animal, like a sheep, then take out that kidney to use in humans, more people could get kidney transplants.

Legal Limits

Many countries have passed laws that restrict research on chimeras. Since 2007, Canada has outlawed any research on chimeras. Image by Giorgi Abdaladze via Wikimedia Commons.

There is a lot of controversy about part-human chimeras. In 2007, Canada passed laws prohibiting some kinds of chimera research. By 2013, both Europe and America made teams to oversee the use of chimeras in research. All of those laws and teams were made to try to keep chimeric research ethical.

Scientists hope that what we learn from part-human chimeras can help us solve current issues. Organ donor shortages may no longer be an issue if we can grow human organs in other animals. We could also get better at fighting diseases if we used part-human chimeras to test out new treatments. Though we might have to wait a few years, chimeras have the potential to change the world as we know it.

Image of chimera rose by Emma.lonying via Wikimedia Commons.

This Embryo Tale was edited by Cole Nicols and is based on the following Embryo Project articles:

Taddeo, S. (2014, November 25). Intraspecies Chimeras Produced in Laboratory Settings (1960-1975). Embryo Project Encyclopedia. ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/8265.

Navis, A.R. (2009, January 21). Beatrice Mintz (1921-). Embryo Project Encyclopedia. ISSN: 1940-5030. http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/1959.

Jacobson, B. (2010, November 17). Nicole Marthe Le Douarin (1930-). Embryo Project Encyclopedia. ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/2303.

View Citation

This rose is a chimera, meaning it has two different sets of DNA. You can see the results of each set here: one set makes the rose white, the other makes the rose burgundy. Chimeras like this occur all the time in nature. Some species even depend on chimerism to survive.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.