Between Bat Brains

show/hide words to know

What's in the Story?

A bat swoops through the clear sky, making a high-pitched clicking as it navigates the night air. It enters the cave and finds its roost, then quickly pulls in its wings to snuggle up next to a whole web of tightly packed bodies. Immediately there's a flurry of squeaks, and the sounds of the roost grow louder. It's still early for the bats to think of leaving the cave, but a few older ones are growing restless. They wriggle out of the pack, spread their wings and fly out, sweeping up into the fading light of the sunset.

Thousands of bats may be packed in to a colony. This image shows just a few bats hanging out in a group on the ceiling of a cave. Image by מינוזיג - MinoZig via Wikimedia Commons.

Behind it all, the calls and chirps continue, bursting up from one side of the cave and then the other. How can any of these bats possibly know who's speaking or tell each other apart? Luckily for you, you find a researcher who can let you in on the secret of what all those neurons in the bats’ brains are saying. In the Science journal article "Cortical representation of group social communication in bats(link is external)," scientists set out to discover if bats know which bats are communicating to them, or if it is just a load of chatter.

Crowded Communicators

Life as a fruit bat can be pretty packed. Egyptian fruit bats often gather in colonies that can have 20 to 9,000 individuals! So they call to each other a lot. This makes them ideal subjects to model human interactions.

Animals might spray urine to mark territory, like this lion. We might also see them rub their faces against objects, or scratch their paws against things to leave their scent behind. Image by Eatcha via Wikimedia Commons.

Communication is a part of life. Bacteria release and read each other's chemicals. Trees use networks of fungal mycelium to share water with other trees in need. And animals might use calls or scent markers to exchange information. For animals, brains are vital to this exchange.

But exactly what happens in our brains when we interact with each other is still mostly a mystery. For example, how can I separate your voice from my voice? After all, I hear both through my ears. And how do we recognize the voices of our friends? That’s exactly what the researchers leading this study wanted to know. They set out to learn if listening bats could figure out which bat was calling and if that changed how they react.

Reading Bat Brains

Researchers gathered a small collection of lab-raised bats and kept them in a dark cage. They then placed small metal electrodes in the front of the bats’ brains, which is their 'social' region. Electrodes can be used to pick up electrical activity and map it as spikes on a screen. The bats’ neurons would fire in a different pattern for each bat call, like each bat had its own theme tune. By comparing the patterns the neurons made while listening, they found that the bats could reliably match up who was who.

After the researchers knew basic recognition was happening, they went a step further. They wanted to know if being able to identify other bats would affect the bats’ interactions. Did the bats use this information to identify their friend groups in the colony?

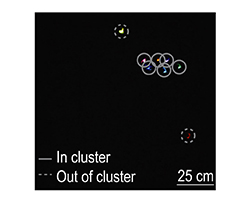

To test this, the researchers placed eight bats in a large cage, away from the rest of the colony. For 14 days they tracked where each bat chose to hang out, and for how long. They did this by attaching LED lights of different colors to each of the bats, and tracking them with a special camera. Some just seemed to prefer to be alone, away from the group.

These bats were called 'out-of-cluster' bats. Those who liked to snuggle in a big pack were 'in-cluster' bats. Remarkably, both how long they stayed and who they hung out with was very regular. Like in a playground at school, everyone seemed to drift to their preferred group when given the chance.

Bat Packs

The scientists placed electrodes in the brains of four bystander bats. By looking at brain activity, the researchers could figure out who the bats recognized. These social groups weren't just basic likes or dislikes, they were visible in the bats’ brains. Different neurons in the bat's brain would light up when they heard specific bats. But sometimes, specific neurons might turn on by accident for the wrong bat. Like a wrong note in a theme tune, it doesn't stop the bat from recognizing the caller, but it makes it less reliable. The scientists found that the neurons would make 34% more mistakes when hearing outsider bats than in-group bats. Bats didn't recognize the out-of-cluster calling bat as easily. But that wasn't all.

Listening bats from the same group as the calling bat (let’s name the calling bat “Bat 1”) would all show similar brain patterns to Bat 1 when it called. The calling bat would label the pattern as 'self', and the listening bats would label the same pattern as 'other - Bat 1'. When bats call to each other, both the listener and caller will show similar brain patterns. But when bats heard in-group bats calling, their brain patterns were 43% more similar. It was harder for any of the listening bats to 'sync' brain patterns with the out-of-cluster bats. This means that out-of-cluster bats might not be as good at social interactions with the rest of the group.

In this study, researchers used bat's brains to show that they do recognize each other. Each bat shows unique neuron patterns in response to the calls of other bats, with more or less accuracy depending on their social group. They also found that brain pattern similarity could predict if the calling bat was part of the listener’s cluster or not. And who knows, maybe these brain similarities can help us learn why we humans can find it so hard to engage with someone from a new social group. Or even to remember their name!

Hanging bat face picture in gold box by Lietuvos zoologijos sodas via Wikimedia Commons.

View Citation

There's still a lot to learn about how bats communicate.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.