Glow-in-the-dark Plants

show/hide words to know

What's in the Story?

Nighttime brings with it darkness. But it also reveals things that can light up in the dark, like the moon and stars. These things that glow in the dark have inspired humans for generations. We have even created things that imitate this glow.

A snap and a shake can give us glow in the dark bracelets, and we can create our own personal night sky with plastic stars. But what if we modify natural things to glow in the dark too? In the PLOS ONE article, “Autoluminescent Plants(link is external),” scientists have figured out how to make plants glow in the dark.This new technology could help us create alien landscapes on Earth, but it also taught scientists about genes that plants share with their ancestors.

Shared DNA

When asked to name something that glows in the dark, people may think of things that artificially glow. But some organisms, like fireflies and some jellyfish and bacteria, can also glow in the dark. Many of these organisms glow in different ways too. Scientists have recently discovered a way to transfer this glow-in-the-dark ability to other organisms that don’t normally glow.

Plants and bacteria have very similar DNA. Perhaps this means scientists can use glowing bacteria DNA to make plants grow. Image by Dejuliot.

All the organisms on Earth are related, and their DNA is made up of the same four genetic building blocks that we call nucleotides. Different patterns of these nucleotides are responsible for the diversity of life we see on Earth. For example, certain patterns code for legs, but slight changes in the order of nucleotides can make the difference between human legs and frog legs.

Plants and bacteria have many DNA similarities, but they also have a ton of differences. Some bacteria can glow in the dark. Plants, on the other hand, can’t glow. But do plants share any of the same DNA that allows those bacteria to glow? They do. Actually, they share more DNA than you might think. Chloroplasts, which are the plant cell organ that allows plants to photosynthesize, actually evolved from bacteria. Chloroplasts have their own set of DNA, separate from the rest of the plant. This DNA is very similar to the DNA of some bacteria.

The Glow Switch

Plants and bacteria share DNA, especially the DNA found in chloroplasts (which make most plants green). This is the tobacco plant, Nicotiana tabacum, which was used in this experiment. Image by Dominik Haenni.

Scientists have learned that because of the similarities between plants and bacteria, certain sections of their DNA can be manipulated or exchanged. Both organisms have the genes that make the proteins which allow the organism to glow. But plants (specifically, their chloroplasts) lack the gene that switches on this protein-making process.

In bacteria, this switch is given the special name of the lux operon. When the lux operon is present, the organism can make special proteins, called luciferase. They can also make other special chemicals known as luciferins. When luciferins are exposed to luciferase, a chemical reaction occurs, and energy is released. We see this released energy as light.

Get it to Glow: Measuring Success

Since the process of bacterial glowing was discovered, scientists have tried to apply it to other organisms as well. One example of this is Green Fluorescence Proteins (GFPs). GFPs are used by scientists to tell if experiments involving gene exchanges have worked. The genes for GFPs are included when scientists insert other genes into an organism’s DNA. If the organism glows after these genes were inserted, then scientists know that the insertion was successful.

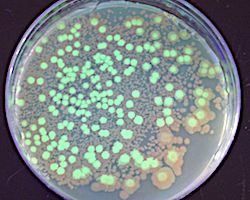

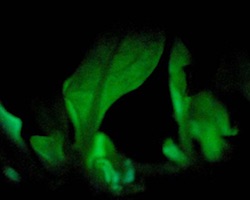

A glowing plant. This is what the successfully modified plants should look like in the dark.

In the same way, modifying a plant’s blueprint to turn on the production of luciferins and luciferase should allow for the plant to glow just like some bacteria do. Scientists tried to insert the DNA for the lux operon (from bacteria) into the DNA of the plants’ sex cells. They predicted that if the DNA for the lux operon was correctly inserted, some of the seeds from that plant would develop into plants that would glow.

When inserting DNA, sections that code for antibiotic resistance are included to help scientists test for the correct product. If scientists expose the modified plants to antibiotics and the plants survive, then they know that they took up the new genes correctly.

The Match and Switch

The lux operon was inserted into the plant’s DNA through a plasmid, a special circular piece of DNA. The code in the plant’s DNA matches the DNA code found on either side of the plasmid gene that is being inserted (in this case, the lux operon). These matching ends allow them to switch—and any DNA between these matching ends will be inserted. After they switch, the plant DNA will have the lux operon in its code.

These insertions were done on the sex cells of a plant, which then developed into seeds for new plants. That new generation of plants was planted and grown normally. Once sprouts had emerged and each plant had multiple leaves, the plants were tested for glowing.

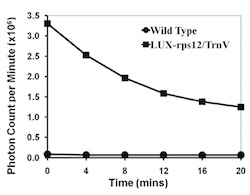

First, the number of photons released by each type of plant was measured. Both types of plants with the lux operon produced more photons than the regular plant. Next, they checked if the plants gave off visible light. When in the dark, the plants with the lux operon did, in fact, glow.

Now that scientists have discovered how to make Tobacco plants glow in the dark, we can apply it to other plants. Scientists also suspect that they could make the light brighter. Glowing plants could one day provide us with nighttime lighting and replace artificial light. This would reduce the amount of energy we consume or provide nighttime lighting to those without electricity. With this discovery we may one day be able to walk around on an alien planet without ever leaving Earth.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Firefly image by Mike Lewinski. Glowing fungus thumbnail (on menu) by Noah Siegel.

View Citation

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.