Benefits of Being Choosy

show/hide words to know

What's in the Story?

Your crush enters the room and your heart immediately starts racing. Your face flushes as you start to talk nervously to your friend. But you aren’t making much sense. Your friend tells you to stop acting so ridiculously.

How does picking your own partner affect your relationship? Couple image by Muramasa.

What is it that makes you feel attracted to this one particular person more than another? Why can’t your friend understand what you see in your crush? Your friend is falling for some other person completely different from the one you like. How do these differences in preference affect the relationships we form?

Measuring the costs and benefits of mate choice is a challenging task. Scientists can’t simply swap partners between two loving human couples to see how well they adjust. In the PLOS Biology article "Fitness Benefits of Mate Choice for Compatibility in a Socially Monogamous Species(link is external)", scientists studied how mate choice affects reproductive success in a bird species.

Sharing the Caring: Social Monogamy

Birds have beaks and wings they use to fly, which makes them seem very different from humans. But some birds aren't as different as you might think.

The zebra finch is similar to humans in some of their relationships. These birds bond with one partner for life and share the duty of caring for their offspring.

They choose their partners in a way that is specific to each individual, meaning different birds do not agree on which bird is most attractive.

Pick a Partner

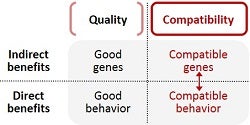

Picking the right partner can be important in many ways. A specific partner can give direct benefits. For instance, if a chosen male brings a lot of food to the nest, this makes the work easier for his female partner. But benefits of mate choice can also be indirect. A wisely chosen partner can pass on good genes that allow offspring to survive better.

At Odds with the Pick of the Pack

Overall, females prefer higher quality partners. Yet, in some species, females do not share their preferences. This suggests that females may choose males that match them best, because they are most compatible. How can one male be more compatible with a female than another?

The genes of a father and a mother mix in their offspring. This means the father’s and the mother’s genes have to work well with each other. Therefore, one possibility is that the genes of a female work better with the genes of one male than with those of another - an indirect benefit.

What about direct compatibility benefits? For instance, coordinating and sharing tasks could be easier with one male than with another. We will refer to the ways two parents interact directly as ‘behavioral compatibility’.

In this experiment scientists wanted to find out if zebra finches that were allowed to mate with the partner of their choice would raise more young (i.e., reach higher fitness) than those that had to settle with a partner they did not choose. And, if this was the case, they wanted to know what caused these differences.

The Dating Game

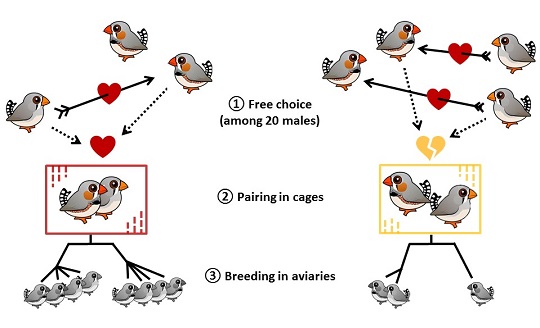

Scientists formed groups of 20 females and 20 potential male partners. Birds could freely choose a mate in a situation somewhat similar to a speed-dating event.

After birds formed pair bonds, scientists swapped the partners in some of the couples (“assigned pairs”) but kept other couples intact (“chosen pairs”). The swapped couples had to settle with the assigned mate while the other birds stayed with their chosen mates. To force the assigned pairs to bond, they were put in cages for a few months until they agreed to become parents. Chosen pairs were put in cages as well.

After all birds had settled with their partners, they were allowed to raise as many chicks as they could over several months. Birds were set in shared breeding aviaries to make sure that they had a setting relatively natural for them to reproduce.

Getting It Right: Reproductive Success

Scientists monitored the fate of every single egg laid by inspecting each nest every day. They removed eggs that did not hatch and any chicks that died. Scientists also followed the growth of each chick until they were all out of their nests and independent from their parents.

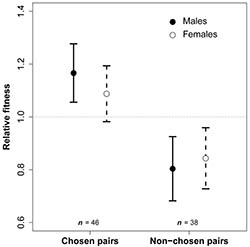

Overall, parents from the chosen couples raised 37% more chicks than parents from assigned couples. This shows that getting a partner someone else wanted does not work as well as getting the partner you wanted.

Measures of Mortality

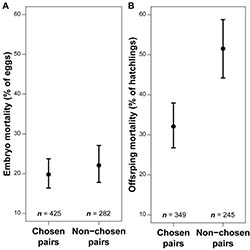

In zebra finches, a developing chick, also called an embryo, can die while it still is in the egg. Embryo mortality is a sign of genetic incompatibility between the two biological parents. To the contrary, after a chick hatches, its survival is only determined by the behavior of the parents that raise the chick. At that point, survival does not necessarily depend on the biological parents. Chick survival therefore depends on behavioral compatibility between the parents raising the chick. Bird parents must work hard constantly to feed their chicks, and chick mortality can be surprisingly high.

Overall, the same number of chicks died before hatching in chosen and assigned pairs. This means the partner of choice did not lead to better genetic compatibility. However, chick mortality was 60% higher if chicks were raised by an assigned couple.

In other words, birds were not as good at raising young when they had to breed with a partner they did not choose. These results imply that, when choosing a partner, zebra finches choose behaviorally compatible mates.

The Happy Couples

So what makes a couple more behaviorally compatible? To answer this question, scientists watched each couple behind one-way glass. They measured behaviors, including how often they were close to each other and if their activities were coordinated.

Chosen couples were more ‘lovey-dovey’ but scientists did not notice more coordination of activities. Females of chosen pairs were more faithful to their partner while females of assigned pairs often were not very interested in mating with their partners. This likely explains why assigned females laid more infertile eggs. Chicks of assigned couples were a bit neglected by the fathers, which may have caused the higher chick mortality.

Overall, chosen couples were more committed to each other and better at raising their kids. The scientists concluded that when you are a zebra finch, what matters most is how your partner motivates and helps you to handle the challenges of having a family.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Zebra finch chicks by Martybugs.

View Citation

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.