Aerial Ant Acrobatics

show/hide words to know

What's in the Story?

The jaw-jump of a trap-jaw ant sends them high into the sky. It would be as if you chomped down and ended up flying over this five-story building.

The sun shines and the birds chirp as you walk through the park, unwrapping the delicious candy bar you just bought. But as you get ready to take a bite, a jogger accidentally bumps you and you drop the candy. Your teeth bite into empty air and—KERPOW! The ground whizzes away as you rocket backward through the sky.

You fly up over the trees, up over the buildings; you fly more than 44 feet straight up in the air (over 5 stories high). As crazy as this sounds, scientists used to think that this sort of explosive accident happened to trap-jaw ants all the time. These insects close their jaws so fast that scientists thought if the ants missed their food, the force of their jaws chomping shut would catapult them into the sky.

An Insect in a Hurry

As its name implies, the trap-jaw ant has a pair of jaws that snap shut like a trap. These mandibles look like big pair of pincers that stick out in front of the ant’s head. Although the jaws may seem awkward, they're incredibly useful. The ants use them to catch prey at ultra-fast speeds. See, the trap-jaw ant has the fastest predatory strike of any animal on the planet: their mandibles can move at 143 miles per hour! The ant can capture the tasty grasshoppers it loves to eat before the grasshopper even has a chance to react and jump away. Talk about fast food.

But where do their acrobatic antics come from? Scientists noticed that trap-jaw ants sometimes fling themselves into the air. Using high-speed video cameras, the scientists found that when this happened, the ants snapped their jaws against the ground. The enormous power of their mandibles hitting the ground sends them flying backward. At first scientists thought these were just mistakes the ants made, but others noticed that the ants would only jump in certain situations. Although the ants are predators, they are also prey. Sometimes they may need to escape from danger.

Escaping a Predator's Predator

Antlions have the perfect name: they are the ferocious lions of the ant world. They are the larval form of a flying insect sometimes called the antlion lacewing. Antlions dig slippery pits to trap their prey and then hide underneath the sand at the bottom of the pit. When ants fall down into the hole, the antlion lunges out of the sand and strikes.

Scientists noticed that the trap-jaw ants seemed to use their powerful jaws to jump when antlions were nearby. Perhaps the ants use their acrobatics to escape from these vicious predators. Like pilots ejecting from a damaged plane, trap-jaw ants might be—POW!—launching away at the first sign of danger. This would mean their mandibles would be a tool for getting food and for escaping to safety. But before this story could be believed, scientists had to test that idea.

Biologists wanted to figure out if jumps helped trap-jaw ants survive an attack from a predator—in this case, the antlion. What kind of experiment would you make in order to test this?

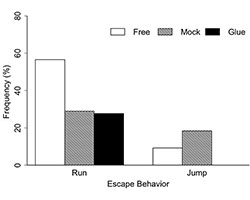

Researchers divided 152 ants into two groups in a laboratory. The first group of ants had their jaws glued shut, preventing them from using jaw-jumps to escape. The second group was made up of normal ants that could use their jaws however they chose. Each ant was dropped into an antlion pit, and the scientists recorded if the ant managed to make it out … dum dum dummmmm... alive. The researchers found that the ants that were free to launch away from danger survived more often. Case closed, right? Wrong!

The Ant Plot Thickens...

See, the researchers noticed that ants from each group often managed to run up the sides of the pit and escape—without using their jaws. Yet the group with their mandibles glued shut were much worse at running. Why would their glued jaws change their ability to run away? Maybe they were panicking from all that glue on their bodies. Imagine if a terrifying giant scooped you out of your house, put big globs of glue on your face, then tossed you into a crocodile pit. You'd be so distracted and shaken, you might not even notice the crocodile sneaking up on you.

To test if the shock from the glue prevented ants from escaping as well, the scientists used a third group of ants called a “mock control.” In science, a control is often used to make sure there are no unintended side-effects going on in the experiment. In this control group of ants, the scientists put glue on the outside of their jaws; the trap-jaw ants might be upset about the glue, but they could still use their jaws. The researchers compared these ants with the glued-shut, can't-use-their-jaws group to see if it was the glue or the inability to escape-jump that caused more ants to be eaten.

When the control group was tested, they were just as slow at running out of the pit as the glued-shut group. However, now that they were free to use their mighty jaws, this group flew through the air more than any other group. They survived much more often than their unlucky cousins that couldn't become airborne. Although it looks like the glue did slow the ants down, they made up for this by jaw-jumping even more.

Phew! It was hard work, but it seems this mystery may finally be solved. Trap-jaw ants use their impressive mandibles to capture prey and to escape from their own predators. But this discovery also brings up new questions. How did trap-jaws end up being used for escape in the first place? Why do some other species of ants with similar trap-like jaws NOT use them for jumping? There are always more questions waiting for new biologists to answer.

In the meantime, check out this high-speed video (shown in slow motion) of a trap-jaw ant falling into an antlion pit and escaping with a jaw jump. The antlion only barely shows its head from underneath the sand.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Trap-jaw ant catching butterfly by Dejean et al., from the PLOS article "The Ecology and Feeding Habits of the Arboreal Trap-Jawed Ant Daceton armigerum." Trap-jaw ant thumbnail by Bernard Dupont.

View Citation

The jaws of trap-jaw ants are dangerous weapons. Here, another species of trap-jaw ant is holding onto a butterfly with its jaws.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.