Fly Immune Issues in Space

show/hide words to know

Gene: a region of DNA that instructs the cell on how to build protein(s). As a human, you usually get a set of instructions from your mom and another set from your dad... more

Larva: the second, "worm-like" stage in the life cycle of insects that undergo complete metamorphosis (like caterpillars).

Phagocytosis: the process used by some cells to engulf and digest foreign objects and dead cells in your body... more

Recognition receptor: a type of structure found on immune cells that helps them detect pathogens.

What's in the Story?

Every day we are exposed to millions of germs, but we don’t always get sick. Our immune systems work hard to protect us from most of the harmful germs out there. But do our immune systems work the same in space as they do here on Earth?

Spending a lot of time away from Earth can affect your health in a number of ways. Image by 272447 from Pixabay.

Although space travel sounds fun, extended periods of time away from Earth comes with some health risks. Stress, changes in sleep patterns, and diet could all affect an astronaut’s immune system. So, it is important to understand how our immune systems react to space travel.

Scientists are just beginning to explore this subject. In the PLOS ONE article “Innate Immune Responses of Drosophila melanogaster are altered by spaceflight,” scientists used tiny fruit flies to try to understand what problems the immune system may have after a space journey.

Flies vs. Humans

As you walk into the kitchen, you see the snack you are craving—a banana. You pick it up and notice a group of fruit flies buzzing around it. But before you try to trap those flies, realize that you are probably more like a fruit fly than you think.

Fruit flies are surprisingly similar to other animals, including humans, in the ways their cells work. Image by Hannah Davis from Wikimedia Commons.

You might think there’s no way you and a fly could be any more different. But the cells of humans and fruit flies work in similar ways. Flies are a model organism for humans, which means scientists use fruit flies to understand more about human biology.

In this study, a group of scientists wanted to understand how space missions affect immunity. So, they studied the effects of spaceflight on both young flies (larvae) and adult flies.

The Senses of Cells

For immune cells to work properly in defending our body, they need to sense when they’ve encountered invaders. Similar to how we use our nose and hands to sense and eat our food, immune cells can sense bacteria in the body.

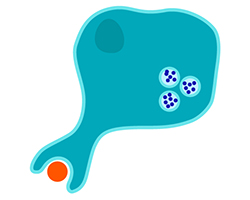

In this illustration, a White blood cell (blue) is "eating" invading bacteria (orange) through a process called phagocytosis.

When new bacteria invade a body, certain immune cells can detect the bacteria early enough to eat the invaders. This process of cell “eating” is known as phagocytosis. If these immune cells do not eat invading bacteria, the bacteria can multiply.

Scientists wanted to know if space travel affects this function of immune cells. To test this, they made immune cells and bacteria different colors so they could easily see and identify them under the microscope.

They attached a protein called green fluorescent protein (GFP) to immune cells in the larvae to make them glow green. They then added E. coli bacteria that glowed red. They did this to see what the cells from space-reared larvae would do with the bacteria. If they worked like normal immune cells do in Earth-reared larvae, the cells should eat the bacteria.

To make sure that they counted only those bacteria that were taken up by the immune cells, scientists also added a blue dye, called trypan blue. The blue would dye any bacteria that were still outside of the immune cells (that hadn’t been eaten). This step made sure that any red glow was only coming from bacteria that were phagocytosed.

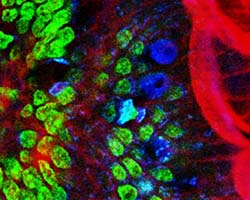

These are not bacteria; they are tissues from a mouse intestine, but this image shows how fluorescence of different cells can be used to figure out what tissues or cells are where. Image from Multi-photon excitation microscopy. BioMedical Engineering OnLine, 2006, 5:36.

Scientists used the red glow to measure the area within each immune cell that was occupied by bacteria over time. Using this method, they could compare how well immune cells were taking up bacteria in both groups of flies.

They observed that the number of immune cells eating bacteria was lower in space-reared larvae, and the immune cells that were active ate fewer bacteria than usual. But why did these cells behave differently?

Genes in Action

Most of your cells have so much DNA that if you stretched it out, it would be over 2 meters long. But we can’t use all of those genes all of the time. At any given time, some of our genes are turned on and some are turned off.

You can think of it in the same way that we can turn the heat in our houses on or off to control temperature. Cells in our bodies have ways to turn genes on or off to control what happens in the cell. This process is called gene expression. Your immune cells will turn on some genes that can help the body fight infection from invading bacteria. But how might spaceflight affect gene expression in immune cells?

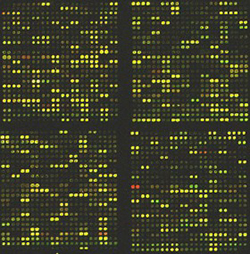

In DNA microarray, small spots of DNA hold sequences that connect to specific molecules. They glow depending on how much of a certain DNA sequence is present. Image by NASA.

If scientists could look at the expression of immune genes in fly larvae raised in space, then maybe they could figure out what causes immune cells to work differently. Scientists used a technique called microarray to look at fly genes. In this technique, DNA is fixed onto a small chip and sent through a machine, to look at the expression level of thousands of genes in a sample at the same time.

As it turns out, some genes related to the immune response were turned off in flies raised in space compared to those raised on Earth. Genes called recognition receptor genes, involved in recognizing bacterial entry, were expressed differently. Scientists found that there were fewer receptors for those genes on immune cells in fly larvae raised in space.

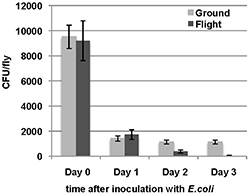

The Bigger the Better

After scientists learned that larval immunity changes in a space environment, they wanted to see if adults were also affected in space. The had two test groups: adult flies raised on earth and adults that had returned from space. Both groups were injected with E.coli bacteria 24 hours after the space-reared group returned to Earth, to see how well they fought off bacterial infection. Scientists observed that spaceflight did not affect the ability of adult flies to fight off a bacterial infection. This suggested that spaceflight could affect aspects of immunity differently during various life stage of the flies.

Does Spaceflight Affect Immune Health?

By studying fruit flies, these scientists were able to make some useful conclusions about changes in immunity after a space journey. They found that the number and function of immune cells in space-reared fly larvae may be reduced when compared to fly larvae on Earth. It’s possible this could also be a problem for astronauts on long-duration space exploration missions.

Understanding how space flight affects immunity may help us figure out how to boost the immune system, prevent diseases on Earth, and suggest potential treatments for astronauts.

Rocket thumbnail image by WikiImages from Pixabay.

View Citation

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Fly Immune Issues in Space

- Author(s): Pooja Kadaba Ranganath

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: April 15, 2020

- Date accessed: January 11, 2025

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/fly-immunity-space

APA Style

Pooja Kadaba Ranganath. (2020, April 15). Fly Immune Issues in Space. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved January 11, 2025 from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/fly-immunity-space

Chicago Manual of Style

Pooja Kadaba Ranganath. "Fly Immune Issues in Space". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 15 April, 2020. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/fly-immunity-space

Pooja Kadaba Ranganath. "Fly Immune Issues in Space". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 15 Apr 2020. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. 11 Jan 2025. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/fly-immunity-space

MLA 2017 Style

Want to learn how spaceflight affects health in humans? Visit Spaced Out Physiology.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.