Hungry Mosquito Habits

show/hide words to know

Epidemic: occurs when new cases of a disease appear in a human population during a given period of time that infects more people than expected based on what we know about the disease.

Pathogen: a virus, bacterium, fungus or parasite that infects and harms a living host.

Vector: a person, animal or microorganism that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism

Zoonotic pathogen: a pathogen that is passed between animals and humans.

What’s in the Story?

Mosquitoes suck blood from mammals and other animals using a small straw-like structure called a proboscis. Image via Ben133uk.

There’s nothing like biting into a nice piece of juicy fruit. Imagine for a moment that your favorite fruit is melon. Even though you can buy certain melons year round, others may be harder to find. When your favorite melon is rarest, you may find yourself choosing to eat some other fruits to satisfy your melon cravings.

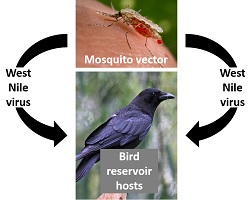

With fruit and many other foods, we tend to eat certain things only during certain times of the year. It turns out that humans aren't the only ones that do this. In the PLOS Biology article “West Nile Virus Epidemics in North America Are Driven by Shifts in Mosquito Feeding Behavior,” scientists studied how the availability of food sources affects the feeding habits of mosquitoes. They believed that changes in mosquito feeding habits affects the spread of West Nile Virus in humans.

West Nile Virus

To begin, let’s talk about West Nile Virus (WNV). West Nile Virus is a seasonal epidemic in North America that is highest during the summer and lasts into the fall. A person can get WNV a few different ways, including blood transfusions and organ transplants. However, most people develop WNV from being bitten by a mosquito that is infected with WNV. About 80% of people who are infected with WNV will not show any symptoms of infection. The other 20% of people that do show symptoms usually will have a fever, nausea, headache, or skin rash.

Little Vampires

You can think of a mosquito as a small fly. However, there is one big difference between a mosquito and a regular fly. Unlike a fly, a female mosquito feeds on blood from other animals. Female mosquitoes have a long appendage on their head called a proboscis that allows them to bite other animals and suck their blood.

Hungry Mosquitoes

Generally, WNV is transferred between mosquitoes and birds. However, scientists noticed that between late summer and early fall the transfer of WNV from mosquitoes to humans became more common than between mosquitoes and birds.

The American robin is the primary food source of the mosquito during early summer. Image by Dakota Lynch.

Scientists knew that the transfer of WNV became more common from humans to mosquitoes, but they didn’t know why. They thought that perhaps this change was due to mosquitoes shifting their feeding behavior from birds to mammals, which included humans. If mosquitoes fed mainly on birds in the summer and then switched to humans in the fall, it could explain the increase in transmission of WNV to humans during that time of the year.

I See the Light!

Scientists studied mosquitoes and their feeding behavior by setting up many light traps. Mosquitoes are attracted to light. They would fly into the traps to get closer to the light source at which point they would be unable to escape. From each trap, the scientists collected only the mosquitoes that had abdomens full of blood. This meant that the mosquitoes had recently eaten, and thus could be tested. The blood in their abdomens was tested and identified as coming from a bird, a mammal, or another animal ("other").

Rockin’ Robins

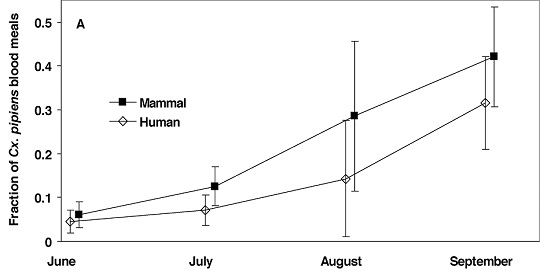

Scientists studied mosquito and bird populations during different times of the year to figure out if a decrease in bird populations would lead mosquitoes to feed more on humans. Scientists found that in the early summer, 51% of mosquitoes fed mainly on one specific kind of bird, the American robin. Additionally, very few mosquitoes had fed off of a human or other mammal during this time.

In late summer and early fall, the population of robins became smaller due to migration habits of the robin. During this time, blood from mosquitoes was more likely to be from a human or mammal. Scientists concluded that the decrease in the number of robins caused the mosquitoes to feed on humans and other mammals more often.

So it seems that the mosquitoes turn to humans for their blood due to the fewer number of robins in the late summer and early fall. However, the scientists reported that the total number of all birds in the area did not decrease. This shows that mosquitoes did not feed on humans more simply because there were fewer birds around, but because there were fewer of their preferred bird, the American robin.

Animal Eating Habits

We may not think that what other animals are eating affects us. However, this study showed that when the availability of animals’ food is changed, it could actually have an influence on people's health. For this reason, it’s important to keep track of the dieting habits of other insects and animals to understand how they might affect humans.

Additional Images via Wikimedia Commons. Thumbnail mosquito cartoon by Wamalero. Mosquito photo by the United States Department of Agriculture.

View Citation

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Hungry Mosquito Habits

- Author(s): Chanapa Tantibanchachai

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: June 19, 2014

- Date accessed: January 11, 2025

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/feeding-habits-hungry-mosquitoes

APA Style

Chanapa Tantibanchachai. (2014, June 19). Hungry Mosquito Habits. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved January 11, 2025 from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/feeding-habits-hungry-mosquitoes

Chicago Manual of Style

Chanapa Tantibanchachai. "Hungry Mosquito Habits". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 19 June, 2014. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/feeding-habits-hungry-mosquitoes

Chanapa Tantibanchachai. "Hungry Mosquito Habits". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 19 Jun 2014. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. 11 Jan 2025. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/feeding-habits-hungry-mosquitoes

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.