Bacteria and Fungi Battle On Bat Skin

show/hide words to know

What's in the Story?

It is autumn and it is starting to get cold outside. You and the rest of your bat colony are preparing to hibernate. As winter approaches, you eat a lot of food to store fat and you settle in for a long sleep. You will need to sleep through the coldest months, when there isn’t any food available. During hibernation, you wake up from time to time to stretch your muscles and you use the energy you’ve saved to do it. As long as you don’t wake up too often, your energy stores will last long enough. But then something goes wrong. In the middle of the winter, you get sick. You don’t feel good, so you wake up several times, which uses up most of your energy. If this keeps happening, you may not survive the winter.

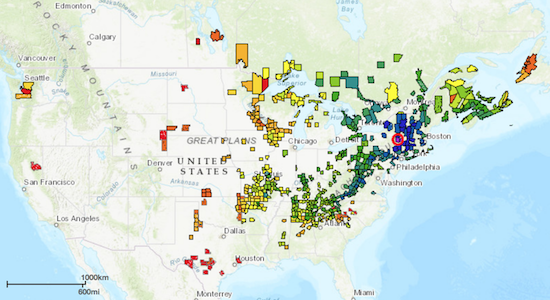

Bats in America have been experiencing this. They are getting sick with white-nose syndrome, a fungal disease that is causing many of them to die. In the PLOS ONE article, "Bacteria Isolated from Bats Inhibit the Growth of Pseudogymnoascus destructans, the Causative Agent of White-Nose Syndrome(link is external)," scientists studied the good bacteria on bats’ skin. They looked at how these bacteria reduce the fungus invasion. Could this be a light at the end of the tunnel for the fight against white-nose syndrome?

Medicine for Wild Animals?

Scientists are working on developing a vaccine to protect black-footed ferrets from a deadly plague carried by fleas. Image by J. Michael Lockhart/USFWS.

When you get sick, you may end up getting medicine from the doctor that you need to take for a few days, or even a few weeks. Just like humans, animals can get sick too. But it is much harder to treat their illnesses with medicine. You can’t easily find all the sick animals in the wild and give them medicine one-by-one over days or weeks. So how can we help wild animals fight diseases?

Scientists can study what is causing a disease, and how to help animals fight diseases with single-treatment medicines. One newer focus of study is the skin microbiota that animals have on their bodies.

Yogurt has millions of good microbes and acts as a probiotic. Image by Takeaway.

Microbiota are good microbes that naturally live either inside or on the outside of an organism’s body. These microbes are important because they help animals stay healthy. When we create medicines or foods that deliver these good microbes, we call those probiotics. We can find probiotics in packed products, such as in yogurt, which has good bacteria that can benefit human digestive systems.

Now scientists want to use probiotics to try to help bats because they are getting sick. White-nose syndrome is a disease caused by a fungus that is affecting bats in North America. The fungus infects bats’ bodies and makes them wake up frequently during hibernation. Bats use valuable energy in when they awake in winter, causing them to run out of their energy stores. Many bats end up starving from the infection and dying, but some have survived the infection. To help bats, scientists had the idea to study the natural bacteria on bats’ skin, to see if it is helping the bats fight against this fungus. Perhaps they could then develop a probiotic that might protect bats from dying.

Rubbing Bats to Get Their Bacteria

Scientists collected bacterial samples from hibernating bats in two locations in New York and two in Virginia. To get the bacteria, they rubbed swabs on the skin of different bats—ten bats from each of four different species. They froze the swabs and took them to the laboratory. There, they put the bacteria on Petri dishes with nutrients to make them grow for three weeks at 9-10°C, the average temperature at which bats hibernate. After the bacteria grew, they separated them according to their color and their growing type. So, each kind of bacteria had their own Petri dish to grow.

Which Bacteria Protects Bats?

Scientists collected the bacteria from bats by swabbing them. Image by USFWS/Ann Froschauer.

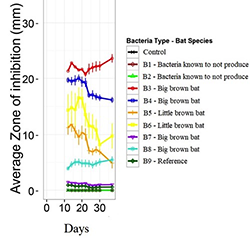

Scientists then took all the different types of bacteria that grew and checked how many of them would be able to reduce the presence of the fungus. They put some fungus spores on Petri dishes and let them grow. Later, they added each type of bacteria to the fungus dishes to see which bacteria would fight the fungus. They compared these bacteria to “control” bacteria: one type that they already knew could reduce the fungus and another two types of bacteria that they knew could not. These then acted as comparisons to see if a certain type of bacteria is successful in fighting the fungus or not. Six bacteria reduced fungal growth, so these were used in further testing. Interestingly, some of these bacteria that help fight the fungus were found on Big Brown Bats that are already known to survive the infection.

Who Will Win, the Bacteria or the Fungus?

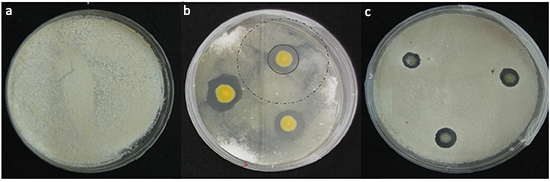

To see how well each of these six types of bacteria reduced fungus presence, scientists did two main tests on them. The first one was to grow fungus at different concentrations in the Petri dish and then add bacteria (“bacterial invaders”). The second was to grow bacteria at different concentrations and then add the fungus (“fungal invaders”). They did these experiments for 37 days, at 9 °C, the temperature at which bats hibernate.

Some of the scientist's treatments. In (a) is fungus growing on a Petri dish without anything added. In (b) is one of the species of bacteria that reduced the fungus; you can see there is a lot of yellow bacterial growth and no fungus grows around the bacteria. In (c) is a species of bacteria that did not reduce the fungus very well.

And the Winner Is?

When the bacteria were added to the fungus (bacterial invaders), the fungus didn’t grow well. When the fungus was added to the bacteria (fungal invaders), the fungus was only able to grow if the bacteria were in small numbers.

Identifying Bacteria that Help Bats

Most organisms in the world have their own unique DNA codes. To identify bacteria, scientists often compare gathered DNA to a database of different known bacteria DNA. These scientists did the same thing. They used a special technique to make millions of copies of the DNA of the bacteria they swabbed off the bats. Then they compared those with DNA of different bacteria previously studied. Now they know which bacteria they might be able to grow to use as bat probiotics.

The Next Steps to Help Bats

These findings are very promising for bats. Scientists think that if they can help the good bacteria grow on bat skin, they may be able to help bats fight the fungus. The next step is to try if this works in the field, where bats live.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Little brown bat with white-nose syndrome by USFWSmidwest (thumbnail) and Moriarty Marvin, USFWS.

View Citation

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.