Illustrated by: Sabine Deviche

show/hide words to know

Can Bees Tell Us How or Why We Form Social Groups?

When scientist Kate Ihle moved to the tropics to study orchid bees and sweat bees in Panama, she didn’t realize that six days a week she’d be commuting to work – by boat. Ihle, who has a fellowship with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Gamboa, Panama, takes a skiff to Barro Colorado Island in the Panama Canal.The island is actually the top of a hill and was formed when the canal was flooded. The island became a biological reserve in 1923 and has become the largest and most extensively studied field research site in the world.

The rainforest of Barro Colorado Island is Kate Ihle's research lab and office 6 days a week.

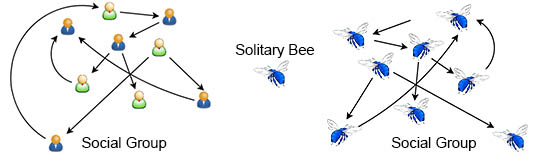

Ihle is interested in what makes some bees more social and others more solitary. This is a question that scientists are also trying to understand about human societies too – how did it happen and why did social groups even come about?

How Do You Study How Societies Are Formed?

Ilhe sets up her experiments with female orchid bees and sweat bees in a field station on Barro Colorado Island – an outdoor laboratory. She first collects nests of these bees, which are usually made inside small rotting branches or twigs. Imagine walking through a forest and picking up every dead twig to check for a nest?

She brings the nest-twigs back to the field lab and opens each one under a mosquito net. Once the twigs are split open, she can see a long channel that the female bee has chewed in the twig, and a series of small containers called cells that each hold a baby bee.

She removes the cells with the baby bee larvae, also called the brood, to raise the bees to adulthood in her lab. By raising hundreds of bees, Ihle looks for links between adult bee behaviors, such as laying eggs and the choice to live alone or with others.

Ihle rears each larva, still inside its original cell from the nest, in a tissue culture plate. The cells are important because each one is packed with food, a ball of pollen and nectar, before the eggs are laid. The egg is laid on this food ball, which will last throughout the growth of the bee larvae, then each cell is closed tight until the adult bee emerges from it. When each new adult bee is ready to climb out of the cell, Ihle puts the new adult females into observation nests made of balsa wood and plexiglass.

She then watches the young female bees excavate tunnels in twigs, build the brood cells in these twig nest, and pack food into the cells with the eggs. Ihle’s observations about the bees include recording how long it takes the new young adult to emerge from the cell, and their whether they are males or females. She also takes notes about which nests her females come from and then follows what choices these new young females make about the nests they build. By watching the behavior of the new females and seeing if they share nests with others or create nests of their own, Ihle hopes to understand if the young bees’ choices match or differ from the same choices that their mothers made.

Ihle’s goal is to ultimately get detailed information over time about sweat bee and orchid bee behavior and see if she can then match up behaviors, such as egg laying and cell provisioning, with what happens with their DNA, their hormone levels and gene expression.

Why Is It Important to Know About Social Groups?

Ihle works closely with two Smithsonian scientists William Wcislo and Mary Jane West-Eberhard, a pioneer in the study of bees and what caused bees to form societies. She is trying to use her bee research model as a tool to answer “why” questions and “how” questions about how social groups arose in animals.

Social groups are found in many animal species including humans and bees. However, not all bees are social like the well known honey bees and their giant colonies. Orchid bees can be solitary and also form small social groups.

In the coming year, Ihle will be looking to see if mother bees influence the size of their daughters by changing the amount or quality of the food that they’re given. Could it be that smaller daughter bees stay at home instead of starting nests on this own? Ihle will also try to affect the size of the emerging female bees by doing experiments as the young bees develop to find help find out more about what controls bees choice to live alone or in a group.

Wild orchid bees on Barro Colorado Island. The male bees are collecting scents in a paper towel placed on a limb in the forest.

Ultimately, knowing what controls the formation of societies in bees may reveal to Ihle and other scientists the rules that govern how and why social groups form. Could it tell us something about our own human society – I guess we’ll have to see what Ihle and scientists like her find out!

View Citation

Kate Ihle prepares some cotton balls with a chemical to attract male orchid bees.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.