Combining Senses

show/hide words to know

What's in the Story?

A person might locate a mosquito on her or his arm by combining information about touch, sound, and sight. Image by James Gathany.

Imagine you are outdoors on a hot summer day. You hear the buzzing sound of a mosquito circling around you and suddenly feel a sharp pinch on the skin of your arm. You quickly locate it by feeling where it is on your skin and directing your sight to that spot at the same time.

The ability to combine information about what you feel and see is not something you are born with. Just as most of our skills, the ability to combine different senses depends on proper development of the brain.

In the PLOS Biology article “Neonatal restriction of tactile inputs leads to long-lasting impairments of cross-modal processing(link is external)” scientists wanted to understand how the brain becomes able to make use of multiple senses, like sight and touch, during development.

The Many Colors of the Brain

The sensory systems of young rats, like these week-old pups, are undeveloped for the first 1-2 weeks of life. Image by Hillary Niemi.

The brain is made up of many cells, called neurons. These cells send messages to each other through special pathways that mainly send one type of information. This helps to make sure that messages travel to the correct area of the brain. For example, the visual cortex is responsible for processing information of what we see and the somatosensory cortex is responsible for processing information about touch. Scientists call the items that activate the nervous system, such as what we see or touch, stimuli.

Sensory information, like vision or touch, use separate pathways. Later when the signals reach the brain they are combined. This process, called multisensory integration, helps the nervous system to better understand what is happening around you. For example, you will better understand a person if you see and hear them rather than if you only see them or just hear them talking.

In this study scientists were interested in how neurons in the visual and somatosensory areas of the brain begin to combine visual and touch information. Scientists used rats to study how the brain becomes able to combine information. Rats are born at a very early stage of brain development and most of their sensory systems are not formed for the first 10-14 days after being born. This gave the scientists the chance to study how the brain begins to combine sensory information.

Neurons Lose their Power

Scientists studied how important early touch and visual information are for developing the ability to combine this information. They did this by trimming the whiskers of rats during the first five days of life. They wanted to know whether trimming the whiskers of a rat during the first five days of life affected its ability to combine senses later in life.

Once the rats were three weeks old and the whiskers regrew, scientists looked at brain activity in response to touch, vision, or a combination of both senses. They were mainly interested in the activity of neurons located within the visual and somatosensory areas of the brain.

Scientists compared the brain activity of rats that had their whiskers trimmed to those that did not. Overall they found that neurons of the visual and somatosensory areas shared less information with each other in adult rats that had their whiskers trimmed. This meant that having touch information a few days after birth was very important for the brain to be able to combine touch and visual information later in life. However, they still did not know why.

Zooming into the Brain

Connections between neurons of the visual and the somatosensory areas develop with age. Because of this, scientists thought that maybe less information was shared between the visual and the somatosensory areas because connections between those areas did not develop correctly.

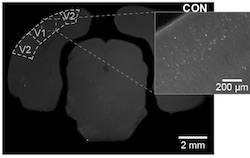

To test this hypothesis, scientists injected fluorescent molecules into the somatosensory cortex. These molecules are absorbed and transported by neurons and allowed scientists to track the path of these neurons.

Once the molecules arrived in the visual cortex the scientists inspected them with a fluorescence microscope. They saw less fluorescent molecules in the visual cortex of rats whose whiskers had been trimmed compared to rats with no whisker trimming. This meant that there were fewer connections between the visual and somatosensory brain regions.

The Rat Playground

Scientists learned that there were fewer connections between the somatosensory and visual brain areas due to the whisker trimming. But they had one last question. Would fewer connections also affect the behavior of the rat?

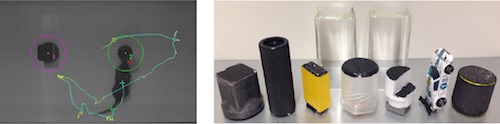

To see whether trimmed rats showed changes in behavior when combining sensory information, scientists placed the rats into an arena with two similar looking objects. Rats are curious animals and are very good at recognizing new versus familiar objects.

The rats explored two objects and then one of the two objects was replaced by a new one. Scientists found that trimmed and non-trimmed rats recognized a new object equally well when they used touch, vision or both senses together. However, early whisker-trimmed rats were less able to recognize the new object when they had to rely on a different sense than the one they used to get familiar with the objects. For example, it was difficult for the rat to recognize the new object with vision if it had explored the first object with touch.

Rats are very curious animals and will explore objects in their environment. Scientists let rats explore a space with two objects, and then changed one of them after a short period of time. The bright-colored line in the left image shows the path of the rat exploring the space, paying much more attention to the new object on the right. The right image shows the different objects scientists gave to the rats to explore.

Making Sense of it All

This study shows that very early in life the sensory pathways start to share information. In addition, the ability to combine senses depends on the presence of sensory input when the brain is developing.

These experiments and their results will help scientists to better understand how the brain works. This research could also lead to the development of treatments for patients that suffer from brain diseases that affect the use of sensory information.

Thumbnail: Sleep-walking neurons: Brain’s GPS never stops working — even during sleep. Image from ZEISS Microscopy (Creative Commons).

View Citation

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.