Illustrated by: Claire Murphy

show/hide words to know

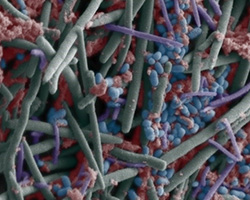

Microbes are all around us. They live inside of us, on top of us, in our food, and in nearly all the places on earth we can think of. Most microbes are friendly – like almost all of the ones inside of our intestines – but a few are dangerous to our health. Despite needing a microscope to see them, microbes make up about 18% of all the living material in the world. We are only beginning to understand how important microbes are to life on Earth.

There are millions of different species of microbes. One of the difficult things about studying them is figuring out which microbes are present, and how many of them there are. Rosa “Rosy” Krajmalnik-Brown is a researcher and professor at Arizona State University who is figuring out how to identify microbes – and how we can use them to our advantage.

Try to imagine all of the microbes on your skin right now. They could be bacteria, archaea (small single-celled organisms like bacteria), fungi (like mold), viruses, or microscopic animals. There are an estimated 100 trillion bacteria on you right now. That’s a pretty difficult number of bacteria to imagine, right?

Microbes to the Rescue

Why might it be good to know what microbes are hanging around? Some of them are good at living on and in our bodies, and some of them are good at eating materials that might be toxic to us. Spilled chemicals might be harmful to animals in the environment (including humans), but microbes might have those same chemicals as a snack! One of the ways we clean up big oil spills in the ocean, for example, is by letting special microbes eat the oil.

Krajmalnik-Brown has studied how to use microbes to clean up spills of many types of chemicals, such as oil and chemical compounds that contain chlorine. She first checks whether the microbes that will eat the chlorinated compound are already in the environment. If they will, she uses a technique called biostimulation to help these microbes grow. If they are not present, she cultures those microbes in the lab before adding them to the environment. This is called bioaugmentation. Biostimulation and bioaugmentation are two approaches to bioremediation. Once done, Krajmalnik-Brown can test whether the microbes started to grow and clean the environment.

The Microbiome: Good and Bad

Krajmalnik-Brown isn’t only interested in how microbes can help the environment outside of our bodies. She is also interested in how they can help inside our bodies. She is especially interested in something called the gut microbiome, which is a way of thinking about all the microbes inside of our intestines. The gut microbiome helps digest our food, and in exchange the microbes get a small bit of the food and a nice, warm, protected place to live.

Krajmalnik-Brown focuses on particular beneficial microbes in our guts that can be important for human health. For example, people with autism have gut microbiomes that are different from people without autism. When some people with autism take pills filled with the gut microbes they are missing, their behavioral and gastrointestinal symptoms may improve. Krajmalnik-Brown is working to figure out what these microbes do in the body that could help prevent autism from developing.

Mining for Microbes

So how does Krajmalnik-Brown actually figure out which microbes are in the environment? All microbe species have DNA, and each species also shares a special gene in common. In her lab, she can remove DNA from all the microbes on a swab to compare all the different versions of this gene that are present.

Microbes are everywhere and hard to see, but with her approach Krajmalnik-Brown is exploring the incredible diversity of these tiny worlds. And these tiny worlds might help us solve important problems that we face, such as treating illness and cleaning up our environments. What tiny worlds do you want to explore?

Mending with Microbes was created in collaboration with The Biodesign Institute at ASU.

View Citation

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.