Illustrated by: Hannah Kalas

show/hide words to know

All around us is an invisible world—the world of microbes. You can’t see these tiny little creatures, but they live everywhere. As you hike through a forest, your feet are walking on top of microbes that live in the ground. When the garbage truck picks up your trash, it takes it to the landfill, which is full of microbes.

Microbes also live inside and on all living creatures, including you. These microscopic microbes eat different things depending on where they live. Whether they are eating dead plants, our trash, or the food in our bellies, they are a constantly doing just that—eating.

As microbes eat and break down material, they release gas. The more microbes eat, the more gas they make. Two of these gases are carbon dioxide and methane. These are both greenhouse gases and add to warmer temperatures on Earth, which is why they are seen as bad gases. Methane can be used as a fuel sometimes or be transformed onto other chemicals, which is why it might be seen as a good gas.

Could we keep microbes from making too much greenhouse gas in the world? And what about trash—could we make microbes that eat our trash faster and provide us fuel? These kinds of questions are what drives microbiologist Hinsby Cadillo-Quiroz in his work.

Microbes and Bad Gas

The Amazon rainforest is wet and full of life. Image by Katarina, via Flickr.

You are walking through a dense rainforest. Pushing vines out of your way, you hop over a large tree root. You land on what feels like a sponge, one that might give at any minute and suck you down to your knees. You carefully pick your way across the squishy peat bog, trying to stay near trees with visible roots you can grab if you fall.

Plants and other matter have been piling up here for thousands of years. The peat isn’t decomposing like you would expect; this is because there is too much water around and in it. So, it just continually gathers into the spongy mass you are walking across.

Peat is important because it traps carbon in the ground. If a peat bog is drained then it will release all that carbon into the air, along with methane. Carbon dioxide and methane are gases that are big climate change contributors, and Cadillo-Quiroz is looking for ways to keep them out of the atmosphere.

This is a chunk of peat, which is a type of soil rich in dead plant material. Image by David Stanley.

Peat is a place where methane is made and stored, but other things make methane too. Little tiny bacteria that live all over can make methane. Cadillo-Quiroz studies how this methane in peat and the microbes that live there can add to climate change, and what factors cause some of these bacteria to make more methane than usual.

When a lot of bacteria make extra methane, it can have a big impact on the local climate. The atmosphere around the place where these bacteria live (either in animals or in the soil) can warm up due to the methane. The higher temperatures can even impact weather patterns so there is more or less rain in an area.

Carbon Balance in Tropical Forests

Clear-cutting parts of the Amazon rainforest releases more carbon dioxide and methane into the air. Image by Matt Zimmerman.

In the Amazon, there is a careful balance of life between the trees and the soil. The trees take in carbon dioxide from the air and give back oxygen through photosynthesis. The soil traps carbon in the ground and slow-acting microbes live in the soil that let a little carbon out at a time. Overall, the forest has been a carbon “sink,” taking carbon out of the air. There are also peatlands in the Amazon, they help trap a lot of carbon and hold in methane. However, when people cut down the trees or drain peatlands for more farmlands, or when big fires sweep across the region, carbon and methane are released instead of stored.

When trees are cut down, the land is exposed to air from the farmers mixing and drying soils, which also lets more oxygen get in the soils. Because there is more oxygen in these clear-cut areas, aerobic microbes work faster in soil and peat, and they release more carbon and methane into the air. That land will then add a lot of carbon and methane to the air instead of taking it out. Cadillo-Quiroz researches how to slow down those microbes and keep the carbon trapped in the soil and peat.

Making Microbes Helpful

Gases that microbes release can be bad for our atmosphere, but sometimes certain gases can be helpful. Microbes exist everywhere, in soil and in peat, as well as in people and in our trash. One of the positive impacts of microbes that Cadillo-Quiroz researches is their ability to eat our trash and turn it into biomethane. In landfills, trash is held under a layer of soil and microbes eat it to help it decompose. Then, the gas that is made by the microbes is collected in pipes and taken to be burned or transformed by other microbes. Burning methane creates energy that generates electricity.

Microbes from landfills (like the one on the left) make tons of methane gas that is often burned on site (on the right). Landfill image by Cezary p on Wikimedia Commons; gas flare by Sirdle on Flickr.

Unfortunately, this is a very slow process. If a chemical is added to help the microbes eat faster, then microbes can get rid of trash faster and make more energy. Cadillo-Quiroz is learning how to make microbes eat trash faster, which results in more good gas for power. At the same time he is learning how to slow the microbes that make bad gas. Microbes are all around us and inside us; Cadillo-Quiroz is trying to use those microbes to help make a better world.

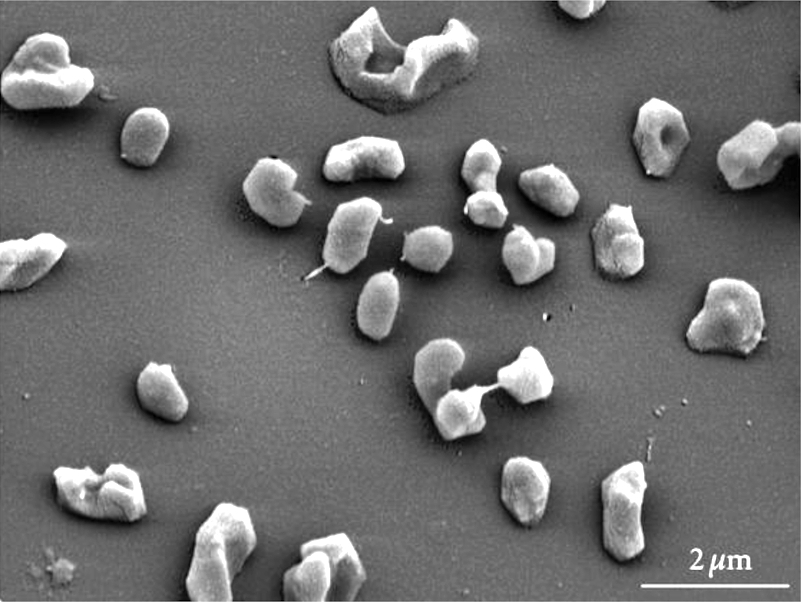

Additional Images from Wikimedia Commons. Methanohalophilus image by Stefan Spring and collaborators.

View Citation

Tiny single-celled organisms, like these Methanohalophilus archaea, produce a greenhouse gas called methane. How does this contribute to climate change?

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.