One-Two Punch for Tuberculosis

show/hide words to know

Colony-forming unit: an estimate of the colonies of bacteria formed in an area of sample.

Efflux pump: a system that moves the toxins and wastes out of your cells.

In vitro: a term from Latin that means 'outside the living organism'; in vitro experiments are those done on tissues outside of a living organism (often in a test tube or petri dish).

In vivo: a term from Latin that means 'within the living organism'; in vivo experiments are those done in a live animal or specimen.

Multi-drug resistant: when a harmful organism, such as certain bacteria, has become resistant to multiple antibiotics.

What's in the Story?

You hold up your pass as you get on the bus and look for a seat. Two more people get on at the next stop, but as the bus driver tries to pull forward, the bus makes a weird noise before the engine turns off. The driver tries to get it started again, but has no luck. Now what? Before the bus can go anywhere, a mechanic needs to figure out what happened. She or he will probably need a few different tools to fix the problem - wrenches and rachets just to name a few. In most cases, using only one tool couldn't fix the problem.

Mechanics must use more than one tool to fix a bus. Image by Adam E. Moreira.

Tuberculosis (TB) is a disease that anyone – big or small, young or old – can catch. You can catch it from someone who has TB if they cough or sneeze around you. In the PLOS ONE article, “Acquired Resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to Bedaquiline,” scientists were trying to figure out why TB becomes resistant to a new drug, bedaquiline (BDQ). This drug was predicted to help treat a lot of people with bad cases of TB, but it was not helping patients as much as was expected. Scientists investigated how the TB cells had become resistant to BDQ and if it should be prescribed with other drugs to help effectively treat TB.

Fighting Tuberculosis

If you’ve never had TB, consider yourself lucky. It can cause a loud cough, fever, and weight loss. It’s a strong and tough infection to fight because many of the antibiotics that doctors give to patients to help them fight the infection stop working. This can happen when the type of TB bacteria being treated becomes resistant to the medicine used for the treatment.

In order to defeat a resistant infection, doctors may prescribe a set of medications rather than just one. Recently, a new drug has been added to the mix. The drug, BDQ, may be a helpful treatment when taken in combination with other drugs. To know which drugs might be useful in this mix, scientists needed to examine how different drugs might work together (or against each other) in the treatment of TB.

Those Darn Mutations

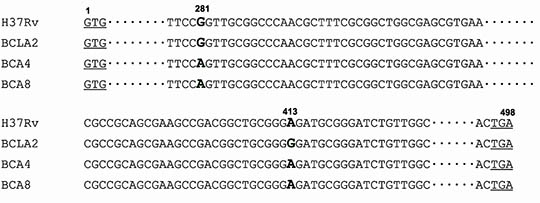

Finding good drugs to treat TB can be difficult. To test a TB drug, scientists investigate what can make it less effective against the bacteria that cause TB. In this experiment, scientists specifically studied the Rv0678 protein and how it affects BDQ. A mutation in this protein affects a type of efflux pump, MmpS5- MmpL5.

The efflux pump is a mechanical part of bacteria. It flushes out the bad stuff (like toxins and waste). The efflux pump is the garbage disposal of the bacteria, but even garbage disposals can sometimes have parts that don’t quite work right.

When the Rv0678 protein has a mutation, more of these pumps are made by the bacteria and they pump out BDQ. The mutation makes it harder for BDQ to fight TB bacteria in the body. This is called efflux-based resistance because it makes it easier for the bacteria to resist the effects of the medication.

Pumping Out the Medicine

Scientists wanted BDQ to work more efficiently against TB, so they looked for a way to fix the problem caused by the efflux pump. They found that when BDQ was given in combination with specific drugs, like efflux pump inhibitors, the amount of the drug needed to fight the bacteria decreased. This is a good thing because you would like to treat the infection with the lowest concentration of drugs possible.

It turns out that the pump mutation worked against the treatment because it caused the pump to move BDQ out of the cell. Efflux inhibitor drugs slow down the efflux of antibiotics like BDQ. As the efflux pump inhibitors slow down the pumps, BDQ is able to finally do its job – to kill the TB cells. Finding out what mutation was affecting BDQ and identifying drugs that solved the problem helped scientists move on to the next step of testing.

The scientists tested a few other drugs to see if they could be used with BDQ to improve its effect on TB. They found that a drug called clofazimine (CFZ) is also pumped out by the same efflux pump. Scientists call this cross-resistance, because one mutation can make the TB bacteria resistant to more than one drug.

When BDQ and CFZ are used together, the drugs will not treat the infection any more efficiently. They can't because they are both pumped out of the bacteria by the same pump. When the Rv0678 mutation happens, it decreases the chance of either drug being effective.

Finish Your Antibiotics

It's important to take your antibiotics as directed, until they are gone.

Using the Right Treatment

Mice that had been treated with a BDQ drug combination for only four months still had TB three months later. It never went away. But the mice that were treated with the drugs for six months got rid of the TB. This shows that the BDQ drug combo was killing off the last of the bacteria between months 4 and 6. This is a good reminder that patients should always finish their prescriptions.

Scientists studying TB treatments found that the Rv0678 mutation can negatively affect BDQ treatment. But the right combination of drugs paired with BDQ can help patients overcome some of the effects of this mutation to treat TB.

When scientists mixed BDQ with efflux pump inhibitors, they found a combination that can help thousands of people struggling with multi-resistant TB to recover. And, as it turns out, science can be like car mechanics in certain ways. Sometimes you have to use a combination of tools (or TB drugs) to fix a problem.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Masked school children by Nikolay Olkhovoy.

View Citation

Bibliographic details:

- Article: One-Two Punch for Tuberculosis

- Author(s): Shima Shiehzadegan

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: June 4, 2015

- Date accessed: January 11, 2025

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/one-two-punch-tuberculosis

APA Style

Shima Shiehzadegan. (2015, June 04). One-Two Punch for Tuberculosis. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved January 11, 2025 from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/one-two-punch-tuberculosis

Chicago Manual of Style

Shima Shiehzadegan. "One-Two Punch for Tuberculosis". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 04 June, 2015. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/one-two-punch-tuberculosis

Shima Shiehzadegan. "One-Two Punch for Tuberculosis". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 04 Jun 2015. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. 11 Jan 2025. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/one-two-punch-tuberculosis

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.