Our Bodies, the Tumor Feeders

show/hide words to know

What's in the Story?

Tumors are kind of like mold. Molds find a nice dark spot to grow—maybe in the corner of the pantry or in the cabinet under the sink. It grows somewhere where it can find the resources it needs, like water and the right temperature. As a tumor grows, it needs resources as well—iron, oxygen, and sugar.

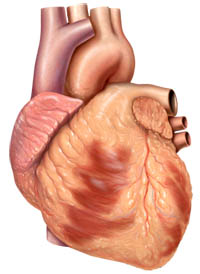

Those are the same nutrients that the human body uses to feed the heart, the lungs, and the brain. So if our bodies need these special nutrients, how do tumors get them? Well, if someone has a tumor, that tumor is fed from that person's very own blood vessels.

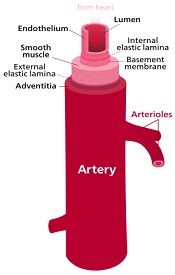

Our blood vessels, like the veins shown here, carry nutrients or waste to and from important body parts. They can also carry nutrients to tumors that can grow in the body.

As a tumor grows, the body will build blood vessels that go right to the tumor tissue, putting nutrients within the reach of the tumor. This is similar to how we might accidentally drop food behind the counter and feed any mold that might be growing there. In the PLOS Biology article, "Generation of Functional Blood Vessels from a Single c-kit+ Adult Vascular Endothelial Stem Cell(link is external)," a group of scientists identified which genes and cells make new blood vessels. If scientists can understand how our bodies are tricked into building blood vessels that deliver nutrient-rich blood to tumors, they may be able to use this information to stop our bodies from building those vessels. That way, they might be able to stop tumors from growing.

Vessels are the Way to My Heart

Blood is pushed through our bodies to our tissues and organs with the help of the heart.

Blood vessels are the tubes that carry blood through your body. Because this is such an important job, these vessels have to be healthy. Your body also has to be able to make more blood vessels as you grow, so your tissues and organs can get the nutrients they need. So how does your body make thin, flat cells that make blood vessels?

The Stem is Where It’s At

Different cells in your body are assigned different jobs. You have skin cells that help protect you from injury, hair cells that make your hair grow, brain cells that help you think and react, and more. But some cells are assigned to the job of making other cells. These are like parent cells, since they make new cells, but we call them stem cells. When your body needs more cells, it can activate a certain type of stem cell so they will make specific cells that your body needs.

So Many Cells, So Little Time

To figure out how your body makes blood vessel cells, called endothelial cells, scientists studied their parent cells. These cells can be found along the walls of blood vessels, where they sit and wait to make endothelial cells. The parent cells are called vascular endothelial stem cells. Anytime the body needs more blood vessels, the vascular endothelial stem cells can divide to make more endothelial cells.

But the thin, flat endothelial cells that are made are quickly used by the body because blood vessels need to be repaired anytime you get a cut or injury, and anytime you grow. This is why the stem cells making endothelial cells are so important. These stem cells can also be dangerous if they start building blood vessels to the wrong places.

Genes Tell the Body What to Do

Hold on… if the stem cells keep making new endothelial cells, won’t the body have too many cells? Actually, no. Your body only makes new cells when your genes tell it to. Your genes are kind of like your parents – your parents tell you when to clean your room and genes tell your body when to build new cells. C-kit genes tell the vascular endothelial stem cells to make more endothelial cells to build more blood vessels, but only when the body needs more. This makes sure the body doesn’t make too many cells.

To find this group of genes, the scientists took samples from vascular endothelial stem cells in mice. They then extracted the DNA contained in these cells. Cells don’t hold a lot of DNA, so scientists have to copy the DNA until there is enough for them to use. To do this, they take the double-stranded DNA, split it in half, and put the pieces in a vial with building blocks called nucleotides.

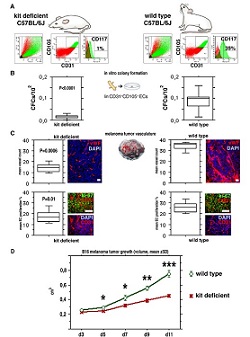

Researchers used two kinds of mice--regular mice that make lots of endothelial cells, and mutant mice, that make very few endothelial cells.

These nucleotides attach to each half in a specific way, re-creating the strand that was removed. The scientists do this again and again, until they have thousands of DNA strands.

The scientists then looked at the order of nucleotides in the DNA to map out all the different genes. But mice have thousands of genes—how did the scientists figure out which ones are involved in making cells for blood vessels?

They compared the genes of mice that made a lot of vascular endothelial stem cells to the genes of mutant mice that didn't make very many vascular endothelial stem cells. By comparing the genes of these two mice types, they figured out what genes controlled the formation of blood vessels. Those genes are called C-kit genes.

Usually c-kit genes tell the blood vessels to grow only when they’re needed. But if cells are exposed to harmful materials, the genes they carry can be damaged and may no longer work correctly. This damage often causes c-kit genes to keep making blood vessels even when the body doesn't need any more. If scientists can find a way to turn these genes off or fix them, they can stop the unneeded growth of endothelial cells. The body would not build blood vessels to feed tumors and the tumors would die.

From Stem Cells to Cancer

Just like food crumbs can feed mold, extra blood vessels in your body can feed tumors. But if we can figure out a way to stop our bodies from creating the vessels tumors use to get resources, maybe we can stop some tumors from growing. Now that scientists have figured out which genes are responsible for building blood vessels, they can focus on ways to change the activation of this gene. This puts us one step closer to stopping tumor growth.

Additional images via Wikimedia:

Blood splatter: Nyki M

Heart in the body: GustavoHCL

Veins in the arm: Colin Davis

Human heart: Patrick J. Lynch; illustrator; C. Carl Jaffe; MD

Artery illustration: Kelvinsong

Lab mouse: Rama

View Citation

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.