Illustrated by: Claire Murphy

show/hide words to know

Being sick is never fun. Strep throat, some ear infections, and some sinus infections can be caused by bacteria. Image by Courtney Carmody.

You wake up in the morning, and your head is in terrible pain. You’ve been sick with a cold, and now everything has gotten worse. Your ears feel like they’re stuffed with jumbo cotton balls, and the cotton balls are growing bigger. Ear infections are so annoying! You know you’re going to be cranky for the next few days … all thanks to an invisible invader: bacteria.

Bacteria are one of your most difficult-to-fight enemies. They’re too small to see without a microscope, but can cause big problems. Your body’s immune system is pretty good at dealing with most bacterial attacks. But every once in a while, they get by your body’s best defenses, causing painful infections and deadly diseases. That’s where microbiologists like Shelley Haydel come in. Haydel studies how bacteria work so that she can use this knowledge to fight them.

Teaching Computers to Treat Infections

One way Haydel is helping people is by training computers to look for bacteria. The computers can learn whether a fluid has bacteria in it, and what kind, by watching them move under a microscope. She helps train the computers by giving them samples that are infected with a known bacteria. It’s kind of like giving someone the answer to a practice test, to prepare them for a real test. Doctors usually need to let bacteria grow for three to four days before they can tell what it is and the best way to treat it. But, computers can tell what the disease is in just two hours, so patients can get treatment faster.

Antibiotics are one way to fight off bacteria. But they can also lead to problems of antibiotic-resistent bacteria. Image by Sage Ross.

By quickly figuring out what bacteria they need to treat, doctors can give patients the right medicine from the start. To cure a bacterial infection, our best bet is to use antibiotics. These are medicines that kill bacteria or slow down their growth. Using the wrong antibiotic, or using them to fight viruses, can lead to resistance. Resistance happens when some of the bacteria that are growing can’t be hurt by the antibiotic. These bacteria survive and reproduce, making a new population of bacteria that are harder to treat. An antibiotic-resistant bacterium is one that we have fewer tools to fight against. Haydel thinks these computers can help doctors be more careful and more accurate with the antibiotics they give to their patients.

Combatting Bacteria with Clay

A few kinds of antibiotic-resistant bacteria already exist, and they are hard to fight. Our most common antibiotics don’t work on them anymore, so doctors have to use harsher ones that have more side-effects. But Haydel found another solution. She found that some kinds of clay can work like a sponge to suck up these bacteria and their toxins. Some clays even have metals in them that kill bacteria. Clays can both get rid of resistant bacteria, and are hard to become resistant to. The metals in the clay hurt the bacteria in many ways.

Clays can be naturally found in many environments. Image by ideepakmathur.

One problem with clays is that they are made by mother nature. Haydel found that clay from the same place might work well one year, but not the next. So, Haydel worked with chemists to make something that works just like the clays, but works the same every time.

Taming Tuberculosis

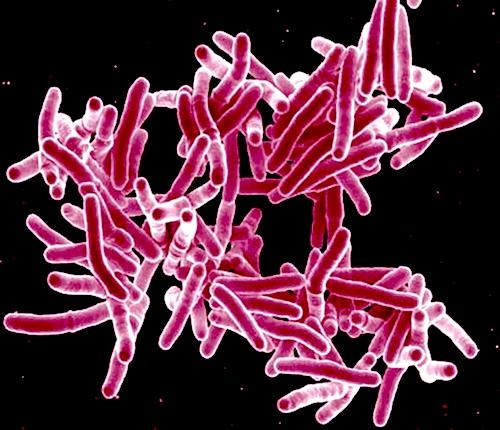

Another way to fight bacteria is to understand them better. Haydel has spent a lot of time studying a group of bacteria called mycobacteria. Some cause infections that hurt healthy skin, and others can cause damage to lungs and eventually death. Most antibiotics work by stopping the bacteria as they make more copies of themselves. Mycobacteria are hard to fight because they copy themselves really slowly. People usually have to take antibiotics for many months before they are cured.

Haydel researches how bacteria work, to find better ways of fighting them. Here, Haydel (right) is working in the lab with an undergraduate student, Jenny Koehl (left).

But Haydel is working to find better ways of stopping these bacteria, by studying their genes. Bacteria have genes in them that work like on/off switches. These genes control a bacterium’s life cycle, and without them, bacteria can get stuck in a certain life stage. Haydel hopes that this knowledge can be used to make medicines that disrupt these switches. That way, even if a person is infected with the bacteria, it won’t grow into a bigger problem, or hurt the patient.

Haydel loves her job because she can be on the front lines of medicine. She works with some of the most dangerous diseases to help doctors find cures. She also teaches students who will be future doctors about how to be careful with antibiotics. Getting rid of dangerous diseases is going to take people with creative new ideas about how we might stop them. Haydel is driven by the knowledge that, by defeating the worst bacteria, she can do the most amount of good.

Smarter Ways to Battle Bacteria was created in collaboration with The Biodesign Institute at ASU.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Mycobacterium image by NIAID.

View Citation

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a dangerous bacteria that causes tuberculosis, a disease that mainly affects the lungs. Shelley Haydel studies harmful bacteria and ways to better fight bacterial infection.

Learn more about research into the bacterial killing properties of clay in our story Isn't it Ionic?

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.