Shimmery Defense

show/hide words to know

Defense: protecting yourself against an attack.

Hive: the place where honeybees store their food, find shelter, and house their young.

Predator: an animal that eats other animals to survive. For example, a lion is a predator... more

Shimmering: a behavior that involves many bees flipping up their abdomens to create what looks like a wave.

What's in the Story?

Giant honeybees pollinate flowers while feeding on nectar. Image by Dr. Farooq Ahmad.

Humans have many strategies for staying safe. At night, you sleep in your house rather than outside where other people or animals can get to you. When you’re on the highway, you drive in a car rather than bicycling through traffic. When you’re at school, you keep your books, phone, and other necessities in your locker or book bag to keep your stuff safe.

But not every animal has those options. Many, like the giant honeybees of Asia, have to live outside where they are more vulnerable to predators. So how do they protect themselves? In the PLOS ONE article, “Social Waves in Giant Honeybees Repel Hornets,” scientists uncovered an interesting strategy that the honeybees use to fend off predators.

A Good Defense

Like many other animals, the giant honeybee builds a structure to live in. Specifically, they build a hive that provides shelter for young and to store food. Many types of bees will purposefully build their hives in places that are hard to find. This helps to keep the bees safe from other animals that might try to eat them, such as wasps or birds.

Giant honeybees build their hives in the branches of large trees. Image by Sean.Hoyland.

Unlike many other kinds of bees, giant honeybees tend to build their hives out in the open. This can make them easy for predators to find and attack. For example, both birds and larger insects like hornets and wasps will fly by the hive and grab bees off the top to eat.

To prevent a potential attack on their hive, giant honeybees have created a tough defense mechanism. They can quickly mobilize a large group of stinging guards that will fly after and attack potential predators. They can also heat their abdomens to more than 100 degrees Fahrenheit. This works to fend off smaller predators, such as wasps, which die at these temperatures. Several bees surround a smaller predator, like a wasp, heating it up until it dies.

This defense mechanism works very well to protect the hive, but it also requires the bees to use a lot of energy. For example, when you face a bully at school, it’s easier and safer to walk away than to run at him or her screaming and punching. If you had to do this dozens of times per day, it would be very tiring. You might even be too tired to eat or do your homework.

In the same way, if the giant honeybees have to defend their hive many times a day they might be too tired to do anything else, like collect food or care for young. Scientists wondered if the giant honeybee might have another way to protect hives in a way that uses less energy.

The Honeybee Shimmer

To answer their question, scientists in Nepal studied the behavior of the giant honeybee. They used video cameras to record two different hives. They wanted to see what was happening in and around the hives.

When watching the videos, scientists noticed an interesting behavior. Dozens of honeybees would sit on a hive and all flip their abdomens up in the air at the same time. Each flip lasted less than a second. This made the hive look like it was shimmering, or moving in a way similar to people doing "the wave" at a football game. But why would they do this?

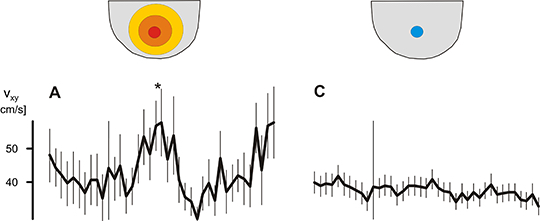

Scientists wondered whether this was a behavior that the giant honeybee used to keep predators away. To study this, they recorded if a hornet was present when the shimmering occurred. If a hornet was present, the scientists also looked at how fast the hornet was moving toward the hive.

Overall, the videos showed that the shimmering behavior happened whether or not a hornet was present. But the number of bees performing the behavior was very different in each context.

If a hornet was not present, only a few bees would perform the shimmer. But if a hornet was nearby, almost all the bees in the hive would show the behavior. The scientists also found that if the hornet was flying more quickly than usual at the hive, more bees would shimmer more often.

Hornet Response

Imagine playing football with your friends. If a big player was running at you very quickly, you would want more of your friends near you to help you stop the other player. You might even jump up and yell to seem scarier. The scientists believe the bees were doing the same thing when they performed the shimmering behavior. But the next question they were interested in was whether the behavior actually kept the hornets from attacking the hive.

To do this, they had to record video of the hornets. If the shimmering stopped the hornets from attacking, the behavior must be working. Scientists found that this was the case. The hornets tended to move away from the hive when the shimmering behavior occurred. This stopped them from flying over the hive and picking up bees to eat.

Shifting Sights

So why did shimmering work to keep the hornets away from the honeybee hive? Scientists think that maybe the movement of the bees makes each one harder to see. And if all the hornet can see is a moving hive, it may become confused. Then it can’t find one bee to grab and eat.

Scientists also thought that when the bees were lifting their abdomens, they looked like they were going to sting. This may also look scarier to the hornet and keep them from moving any closer. Both of these things might make a hornet think twice before attacking.

Shimmering to Safety

It might not make sense to us for an animal to build its home in the open when there are other, safer options. But giant honeybees are the second oldest known bee species. So they must be doing something right. Overall, this shimmering behavior shows that the giant honeybee has developed several different strategies to scare off predators while avoiding an attack.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Honeybee image by Fir0002. Vespa hornet image by Gideon Pisanty. Video of shimmering behavior taken from the PLOS article supplementary information.

View Citation

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Shimmery Defense

- Author(s): Melinda Weaver

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: January 18, 2016

- Date accessed: January 13, 2025

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/shimmery-defense

APA Style

Melinda Weaver. (2016, January 18). Shimmery Defense. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved January 13, 2025 from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/shimmery-defense

Chicago Manual of Style

Melinda Weaver. "Shimmery Defense". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 18 January, 2016. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/shimmery-defense

Melinda Weaver. "Shimmery Defense". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 18 Jan 2016. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. 13 Jan 2025. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/shimmery-defense

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.