Money Matters: How Wealth Affects Offspring Success

show/hide words to know

What’s in the Story?

In some households, are resources split unevenly between children of different sexes? Image by visualpanic.

You and your sibling watch as your mom goes to get you both a treat. She opens the cookie jar and makes a strange noise. It turns out there’s only one small cookie left. It isn’t enough to split, so who gets the cookie? You? Or your sister or brother? Sometimes it might seem that either sisters or brothers get better treatment from their parents. While this isn’t always the case, in some societies, it may very well be true. The difference between how daughters and sons are treated may be greater in families that have more children.

In the Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health article, “Socioeconomic status determines sex-dependent survival of human offspring(link is external),” researchers studied how household wealth (rich vs. poor) may affect how many sons or daughters a family will have. Whether a household is rich or poor may determine the number of children, the sex ratio of the children (the percentage of sons or daughters), and their survival rates.

Predicting Paternal Investment

Evolution is how organisms (including humans) change over very long periods of time. Some traits that help organisms to survive and reproduce are passed on to future generations. Survival and reproductive fitness depends on how well organisms are “adapted to” or “fit” their specific environment.

The Trivers-Willard hypothesis suggests mammals may be able to adjust the sex ratio of offspring (number of sons vs. daughters) they produce in response to environmental conditions. Meerkats image by Francis C. Franklin.

In evolutionary biology, the Trivers–Willard hypothesis suggests that female mammals (such as humans) produce more sons or more daughters in response to their environment. The Trivers–Willard hypothesis suggests that there will be more investment in sons by parents in good conditions (such as when food is easy to find). While in nature, sex ratios (number of males to females; M:F) are often 50:50, evolution will sometimes deviate from this if one sex has a better chance for reproductive payoff.

Many humans practice monogamy (only one mate), though most human populations are polygamous. This means that a person may have multiple mates (or wives or husbands). In most polygamous societies, men will marry and mate with multiple wives. But not all polygamous men can have the same number of wives. In these societies, men with more money can afford to marry more wives and have more children. Thus, sons have a better chance of having more children in a rich household than a poor household. Rich households may therefore favor sons over daughters.

In this type of polygamous population, sons can have many children through the marriage of multiple wives. That ability will create strong competition among males. Low-condition males in a polygamous society will likely have few or no wives.

What effect might this have on following generations? In good conditions (i.e. higher household wealth), parents that have more sons (that, in turn, have more sons) will have more descendants running around. Because of this, parents are under selection for mutations that would lead to more production and investment in sons rather than daughters. Parents that have those mutations will be more successful, and those mutations would spread through the population faster.

An opposite prediction holds for poor-condition parents. Because their sons cannot compete, and so reproductive success would be low, selection will favor investment in daughters. If poor-condition parents have more daughters, those daughters will be more likely to mate and have children than poor-condition sons.

The Trivers–Willard hypothesis effects have been observed in many animals; however, most findings for human studies have mixed results. This is because most of the human studies were performed in monogamous populations, where partners are married to only one person at a time. The Trivers–Willardeffects are not expected in a monogamous population because there is likely not a large difference in reproductive output of sons and daughters. In polygamous societies, you would expect to see a difference in reproductive output of sons and daughters because of the strong competition among males to get multiple wives.

Rich Man Poor Man

The polygamous society studied was in the eastern African country of Ghana, shown here in dark blue. Image by Alvaro1984 18.

Evolutionary biologists studied 28,994 individuals in a polygamous society in rural Africa, in the Upper East Region of Ghana. The authors investigated offspring differences in poor and rich households to test the hypothesis that rich households would benefit more from sons than from daughters. According to the Trivers–Willard hypothesis, parents will invest more in the offspring of the sex that has the best chance of having their own children someday.

To determine the wealth of a household, individuals in the study from several different villages, answered questions about their belongings, including motorbikes, bicycles, and livestock. From these items, a wealth index was calculated. Poor households were defined as the poorest 50% of the households, and the rich as the richest 50% of households.

Household Wealth and Offspring Survival

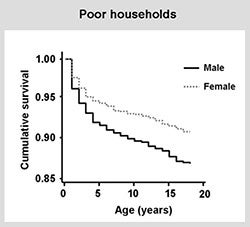

Offspring survival was determined for 16,632 individuals under the age of 18. In the poorer households, male children were less likely to survive to age 18 compared to female children. In the richest households, male and female children were equally likely to survive to age 18.

In poor households, the total number of lifetime offspring was 3.4 for men and 2.7 for women. In rich households, the total number of lifetime offspring was 6.0 for men and 3.1 for women. The greater number of offspring for men in rich households compared to men in poor households is largely because richer men can afford more wives.

Is it Better to be Born a Son or a Daughter?

In the Upper East region of Ghana, 48% of the populations are polygamous. The researchers discovered that in this polygamous society, the Trivers–Willard hypothesis seems to hold true. They reported that there were more sons in rich households, and sons had higher survival rates and body weights compared to sons in poor households.

The observed sex differences in these rich and poor households could be the result of higher death rates of sons in poor conditions. The mortality rates in poor and rich households show that in poor conditions, sons have a much higher chance of death. Thus, the observed differences in survival based on sex may be due to a health difference that puts sons at more risk in poor households, rather than due to the proposed Trivers-Willard hypothesis of parent bias for a specific sex ratio. In either case, the result is the same; in this polygamous society, sex matters. Sons are better off in richer households.

EvMed Edits are sponsored by ASU's Center for Evolution and Medicine.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Ghana children image by USAID. Newborn in menu thumbnail bySCA Svenska Cellulosa Aktiebolaget.

View Citation

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.