show/hide words to know

Rods and Cones of the Human Eye

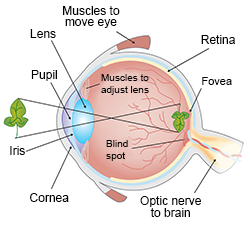

You can see in the drawing on the left that the back of the eye is lined with a thin layer called the retina. This is where the photoreceptors are located. If you think of the eye as a camera, the retina would be the film. The retina also contains the nerves that tell the brain what the photoreceptors are "seeing."

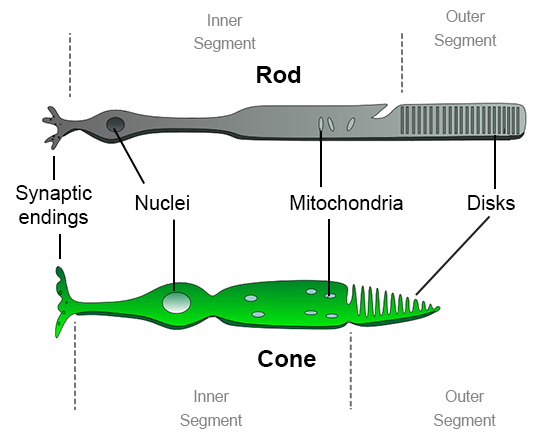

There are two types of photoreceptors involved in sight: rods and cones.

Rods work at very low levels of light. We use these for night vision because only a few bits of light (photons) can activate a rod. Rods don't help with color vision, which is why at night, we see everything in a gray scale. The human eye has over 100 million rod cells.

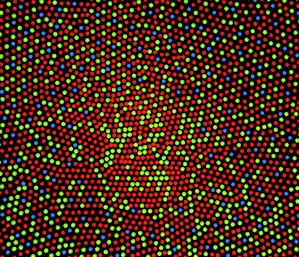

Cones require a lot more light and they are used to see color. We have three types of cones: blue, green, and red. The human eye only has about 6 million cones. Many of these are packed into the fovea, a small pit in the back of the eye that helps with the sharpness or detail of images.

Other animals have different numbers of each cell type. Animals that have to see in the dark have many more rods than humans have.

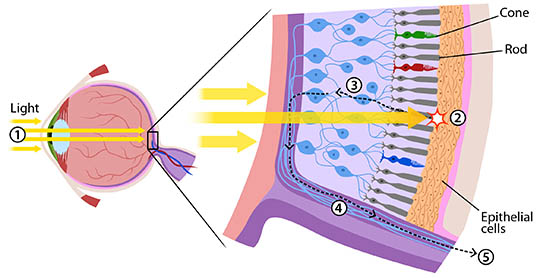

Take a close look at the photoreceptors in the drawings above and below. The disks in the outer segments (to the right) are where photoreceptor proteins are held and light is absorbed. Rods have a protein called rhodopsin and cones have photopsins. But wait...these are stuck in the back of the retina. That means that the light is absorbed closer to the outside of the eye. Aren't these set up backwards? What is going on here?

The "backwards" organization of rods and cones is helpful for a few different reasons.

Cell orientation makes it easier to recycle parts. Image by HuBoro.

First of all, the discs containing rhodopsin or photopsin are constantly recycled to keep your visual system healthy. By having the discs right next to the epithelial cells (retinal pigmented epithelium: RPE) at the back of the eye, parts of the old discs can be carried away by cells in the RPE.

Another benefit to this layout is that the RPE can absorb scattered light. This means that your vision is a lot clearer. Light can also have damaging effects, so this set up also helps protect your rods and cones from unnecessary damage.

While there are many other reasons having the discs close to the RPE is helpful, we will only mention one more. Think about someone who is running a marathon. In order to keep muscles in the body working, the runner needs to eat special nutrients or molecules during the race. Rods and cones are similar, but instead of running, they are constantly sending signals. This requires the movement of lots of molecules, which they need to replenish to keep working. Because the RPE is right next to the discs, it can easily help reload photoreceptor cells and discs with the molecules they need to keep sending signals.

Now that we know how these photoreceptor cells work, how do we use them to see different colors?

We have three types of cones. If you look at the graph below, you can see each cone is able to detect a range of colors. Even though each cone is most sensitive to a specific color of light (where the line peaks), they also can detect other colors (shown by the stretch of each curve).

Since the three types of cones are commonly labeled by the color at which they are most sensitive (blue, green and red) you might think other colors are not possible. But it is the overlap of the cones and how the brain integrates the signals sent from them that allows us to see millions of colors. For example, the color yellow results from green and red cones being stimulated while the blue cones have no stimulation.

How Do We See the Color White?

Our eyes are detectors. Cones that are stimulated by light send signals to the brain. The brain is the actual interpreter of color. When all the cones are stimulated equally the brain perceives the color as white. We also perceive the color white when our rods are stimulated. Unlike cones, rods are able to detect light at a much lower level. This is why we see only black and white in dimly lighted rooms or while out viewing a star-filled night sky.

Are Carrots Good for Your Eyes?

Let's take a minute to talk about vitamins. The pigment molecule attached to the proteins in photoreceptors is called retinal. When retinal absorbs photons, it gets destroyed in the process. In order to regenerate more retinal, your body needs Vitamin A. Carrots are one food that is high in Vitamin A. This makes them good for your eyes, but don't think they will make your eyesight better. While carrots are good for the health of your eyes, they won't make you see better or let you ditch your glasses or stop wearing your contact lenses.

Images:

Eye anatomy illustration from Beginning Psychology (v. 1.0) via Creative Commons (by-nc-sa 3.0). Labels modified for this page.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons

View Citation

This is an illustration of the distribution of cones in the human eye in the fovea. If you look toward the center there are few blue sensitive cones.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.