Evolution Detective: The Case of the Broken Bones

show/hide words to know

What's in the Story?

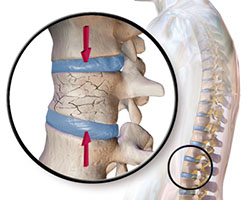

A human spine showing a vertebral fracture.

Across the country, some people are developing cracks in their back bones. It’s up to you, the world’s foremost detective, to solve the case. The young man at the door notices the expression on your face and says, “Don’t give up! If anyone can fix this monkey business, it’s you, Detective.” Wait! Monkey business… monkey… Something clicks into place in your mind. “Not just monkeys, good man,” you say, suddenly beginning to smile, “Apes!”

Although they aren’t licensed detectives, scientists are on a mission to discover the mysterious origins of spontaneous vertebral fractures in the PLOS One article, “Human Evolution and Osteoporosis-Related Spinal Fractures(link is external).”

The Bones Behind Spinal Fractures

Over 700,000 people in the United States report suffering from something called spontaneous vertebral fracturing every year; scientists think the real number of cases is much higher. This fracturing occurs when the bones in your back (also called vertebrae) suddenly crack; this can happen even without a fall or accident taking place. Scientists and doctors have a few clues to the culprit, however.

Such bone breaking doesn’t happen to everyone. It almost exclusively happens to elderly people with a disease called osteoporosis. As many humans age, their bones naturally become weaker and lighter. Lifestyle choices—ones that are easy to avoid—such as not exercising, not eating enough calcium, or not getting enough vitamin D can speed up that bone loss. However, if your bones lose too much weight, they can become more hollow on the inside—it kind of looks like swiss cheese—and we call it osteoporosis. Doctors think that these fractures happen because bones in patients with osteoporosis lose too much of their strength. Yet a bit more evidence complicates the situation…

The Evolutionary Puzzle of the Backbone

Scientists found the second clue to why spontaneous vertebral fracturing happens in humans’ closest living relatives: other apes. As humans, chimpanzees, and other apes continue to age past adulthood, their bones often become lighter and weaker.

However, in all ape species alive today, humans are the only species that suffers from the cracking. Even if the other apes have their bones lose mass and weaken, their bones don’t suddenly break. Researchers realized this fact implies that something special about humans must be increasing our risks of vertebral fractures.

To test whether human backbones and vertebrae are somehow different from those of the other apes, scientists gathered vertebrae from young adult gibbons, orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans. Don’t worry though: no humans or other apes were harmed in this study. The scientists visited several natural history museums across the country to borrow and test the ape skeletons that the museums already owned.

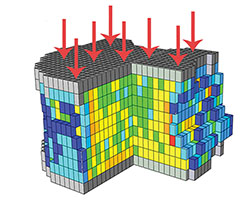

The scientists then did exactly what investigators do in crime movies. They used CAT scans (also called CT scans) to X-ray the bones and create digital 3D versions of the bones. That way, computers could analyze the shape of the bones— both inside and out! They applied digital forces to the computerized bones, pressing and squashing them to estimate the strength of each bone from each species. Using only these bones, they could even reconstruct the weight of each animal when it was alive.

A Human Problem

It turns out that for our size, human vertebrae are wider and larger than the vertebrae of chimpanzees, gorillas, and the rest. But then why are we the only ones to develop these dangerous vertebral fractures?

Even though our bones may be larger, they aren’t as strong: inside the bones, they are less dense and the layer of extra-strong shell that covers our bones is thinner than in other apes. Our bones start out more porous—more “swiss cheese-like”—so even though all apes lose bone weight as they age, human osteoporosis patients end up with extra-flimsy backbones. (If you really want to impress friends and family, you can use the phrase “reduced vertebral trabecular bone volume fraction” to describe our light-weight, flimsy bones.)

But our detective from earlier wouldn’t be satisfied just yet. We still don’t know WHY humans have larger, but less dense, vertebrae. Luckily, our scientists study human evolution: they look to our past and our close ape relatives to explain situations we find ourselves in today. They noticed that the apes studied all move around in different ways: gibbons swing from branch to branch with their arms, orangutans climb and swing with four limbs, gorillas and chimpanzees walk using their feet and the knuckles of their hands, but only humans are always bipedal. We are the only apes that spend most of our time walking around on two legs.

The Weight of Walking

Previous studies have shown that walking upright puts more stress on your back and your feet: each time you take a step, all your weight and force channels down into the heel of one foot. It’s very high impact and it takes a toll on your bones. Other apes don’t have this problem, because walking on four limbs or climbing trees spreads out that force and divides it among all their arms and legs.

In fact, the bones in our legs have changed to help with our high impact way of moving. Our leg bones became larger and more porous compared to the leg bones of other apes. Wider, larger bones spread out the force instead of concentrating it, and more porous bones act as better shock absorbers too. Larger but more porous bones, where have we seen that before…?

Aha! It looks like we may have found the culprit! Our scientists found that human vertebrae were ALSO larger and more porous than the same bones in apes. Perhaps the same things are happening in our backs and in our legs: to decrease all that high impact stress from walking around on two legs, the bones in our backs and legs become larger, but less dense.

Although this helps make walking safer for most of our lives, it could potentially cause problems in our old age if we get osteoporosis. It’s what scientists call a trade-off between good and bad situations: even though there are problems with large, wide, porous bones, the benefits of having them outweigh the costs for our bodies. Now that we know why people are getting those spontaneous vertebral fractures, perhaps we can put more focus on fixing the problem once and for all.

EvMed Edits are sponsored by ASU's Center for Evolution and Medicine.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Embryo spine by Ed Uthman.

View Citation

The developing spine of a human embryo.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.