It's Raining Cats and Dogs... and Mushrooms

show/hide words to know

What's in the Story?

In the forest, light passes through the trees and shines onto dark brown leaves and pine needles on the ground. As you walk over the leaves, you hear them crunch beneath your feet. Occasionally, you see a clump of smooth white caps, like buttons, below the rotting leaves. Along your path an old tree has fallen and all around the stump you notice similar rings of bright orange buttons popping up from the decaying bark.

An artist's conk mushroom growing in the forest. Image by George Chernilevsky.

These small organisms, called mushrooms, do a lot of important things: they decompose dead matter and wood, have healing properties, and they are one of the three most popular pizza toppings. Scientists also think mushrooms serve another important purpose – they may help make it rain. Mushrooms create tiny spores for their own reproduction, but these spores also help to collect water in the air and form rainclouds in the sky.

In the PLOS ONE article, “Mushrooms as Rainmakers: How Spores Act as Nuclei for Raindrops(link is external),” scientists used powerful microscopes to zoom in and see how mushrooms might be making rain.

Mushrooms Are Everywhere

Mushrooms are all around us, in the grocery market, in our gardens, along the sidewalk, and sometimes growing under our kitchen sinks. Most mushrooms have a stem covered by a smooth cap and beneath the cap there is a stack of paper-thin flaps called gills. Mushroom gills look very similar to the gills of a fish. The gills hold the tiny reproductive unit of the mushroom, the spore.

Spores are so small they look like a thin layer of dust covering the gills. Mushrooms launch their spores into the air so they can drift over to new areas where they will then fall back to the surface and grow. What we didn’t know, until recently, is that while these spores are in the air, they can attract tiny water drops that gather together to help clouds form in the sky.

You might be thinking - mushrooms are small and their spores are microscopic, so how could they form big rainclouds? Well, a single mushroom can create and release billions of spores every day. Even though they are tiny particles, 50 million tons of spores are released into the air every year. That is equal to the weight of 1.25 million semi-trucks floating by in the sky. How, exactly, do these spores help make rain? That’s what one group of scientists wanted to find out.

Big Microscope, Tiny Particles

If mushroom spores are so small, how can scientists see and measure them? Scientists looked through a powerful microscope, bigger than any microscope you have used in your own science class, to zoom in to the smallest mushroom spores. The mushrooms were kept in sample chambers that had air running through them. This let the scientists control the environment around the mushrooms. They changed the amount of water in the air to see what would happen when the air had the same amount of moisture as a cloud in the sky.

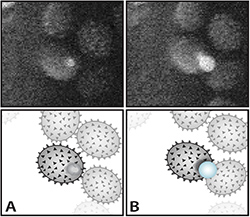

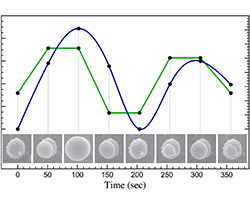

Scientists didn’t look at just one type of mushroom. Instead, they collected seven unique types of mushrooms with differently shaped spores. Some spores looked like cubes, seeds, warts, or stars. To get the spores, they had to pinch the mushrooms until the spores were released like a cloud of powder. While under the microscope, they changed the amount of moisture in the air so they could see the mushroom spores attract water droplets from the air.

How Do Raindrops Form on Mushroom Spores?

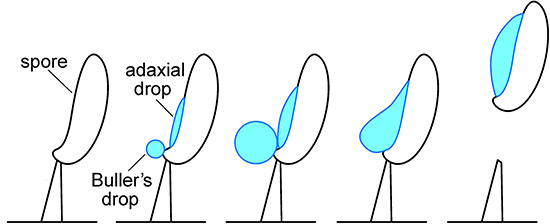

A long time ago, one scientist named Buller noticed that mushrooms sometimes form drops of water between their gills. Because he was the first to think about this, they named this drop of water after Buller. It turns out that these water drops are actually forming on the spores. Once Buller’s drop forms on the edge of the spore, it sets the spore in motion. Like jumping off a swing, the spore is then launched into the air where it drifts away in the wind to join millions of other spores. The spore can launch as fast as four miles per hour – the pace of a brisk walk.

This is an example of how Buller’s drop forms on the very tip of the mushroom spore. As Buller’s drop begins to collect more water vapor, it combines with the smaller drop of water that is facing the mushroom (the adaxial drop). When this happens, the motion of the liquid, like sloshing water in a bucket, gives momentum to the spore. The momentum helps it to launch into the atmosphere.

Condensing into Clouds

Have you ever left a cold drink out on a hot day? You probably noticed that when you picked the drink up again it was covered in water. The change in temperature between the cold glass and the hot air outside of the glass causes the water vapor in the air to slow down and become liquid again.

The scientists found that just like water outside of the glass, the mushroom spores floating in the air attract new drops of water to join it. When billions of spores in the air attract billions of drops of water, then rainclouds form.

Mushrooms in the Clouds

In places where it rains all the time, like tropical rainforests, there tends to be a lot of mushrooms. This could be because the rain encourages the mushrooms to grow and the mushrooms release spores that help it to rain more. Tropical rainforests occur in places where wind from the ocean is carried over to the land. This brings fresh new air to be converted to clouds. However, in order to rain, the clouds need something to condense on, but there might be very few nuclei in the air above pristine forests. Fortunately, mushroom spores, along with other tiny particles like pollen, are abundant in the atmosphere. For this reason, the spores make up an important source of cloud condensation nuclei – which helps rain drops to form. When it rains in tropical forests, the drops of water that fall on the mushroom caps help to push new spores into the air, so they might fall again as rain later.

So next time you are caught in a big rainstorm, don’t turn to the old saying “it’s raining cats and dogs.” Instead, let your friends know that it might be raining mushroom spores, too.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Shaggy scalycap mushroom by Dan Molter (shroomydan). White mushroom (Oudemansiella canarii) image by Ian Dodd (kk).

View Citation

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.