Illustrated by: Shireen Dooling

show/hide words to know

You are hiking through the forest and you notice a patch of ferns off to your right. Their segmented leaves are layered one on top of another, with the top ones still unfurling as they grow. Dappled light wavers over them, providing the sunlight they need to make food.

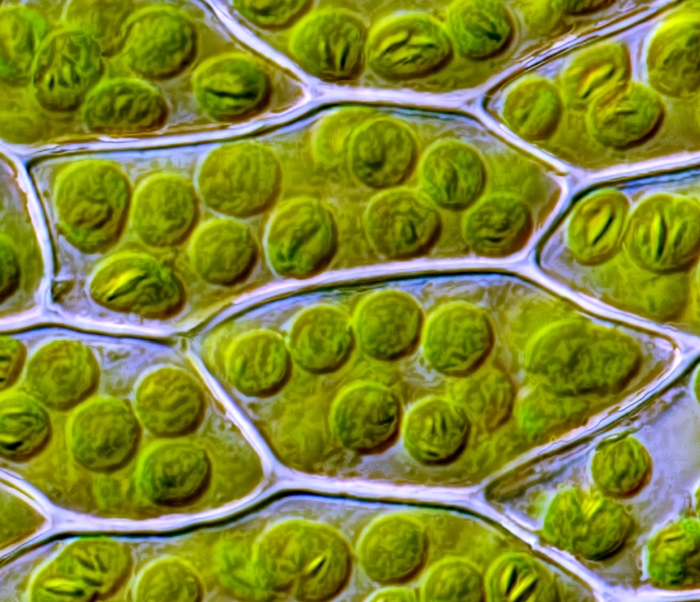

Plants can make their own food from sunlight. They do this through the process of photosynthesis. Image by Hans Kellner.

The tiny cells in the leaves are doing their jobs. They take in sunlight, carbon dioxide, and the water the plant has absorbed. Then they make oxygen and carbohydrate molecules that the plant uses for food. The cells in these plants, and all plants, are very different from the cells in your body. However, all cells have jobs to do to keep living things alive and functioning.

Petra Fromme has been interested in cells since high school. At first, she wanted to study cancer cells, but turned to plants when she found she didn’t like using animals for research. She has spent her career exploring different cells and finding out how they (and their different parts) work.

Fromme first researched photosynthesis in college. This tiny world drew her in, and she started her career exploring how plants use light to make their food and energy. Her research focused on ATP synthase, a tiny special protein, or enzyme, that helps create energy in cells. She was interested in how the ATP synthase enzyme is organized, and how it creates and transfers energy. Early in her career, Fromme became an expert on the different parts of photosynthesis.

Plant Cells

Plants don't just provide us with food and help us to have clean air to breathe. They also may help us design better products that can harness energy from the sun. Image of solar panels by ChristofferReimer.

Fromme finds this field important for many reasons… first of all, we eat plants; the other living things some of us eat also eat plants. As if that wasn’t enough, plants also make some of the oxygen that we breathe. But Fromme thinks plants can be helpful in another way as well. She is interested in how our understanding of photosynthesis can be used to help people. For example, when plants are taking in light to make food, their membranes are charged like batteries. Researchers are looking at plants to come up with new ways to store energy to make solar cells or batteries. But while Fromme was trying to study photosynthesis, she ran up against a problem other scientists were having.

One day, she was working with the free electron laser microscope. Fromme placed her prepared sample in the microscope. She then went to her computer and gave the command to fire the laser. Her goal was to see the cells in action. In a tiny fraction of a second, the laser fired and the process completed. However, Fromme did not get the images she wanted. This is because the laser destroyed her sample before images could be taken.

Lasers!

When you study tiny structures, you have to do it with an electron microscope. But these microscopes would instantly destroy any samples that make oxygen. This means researchers couldn’t get pictures of the process of photosynthesis. Fromme was frustrated by this and decided to fix the problem.

Problems with X-rays

We usually think of x-rays as something a doctor uses to see a broken bone. However, scientists also use x-rays in free electron lasers. X-rays are an electromagnetic wave, like the light from the sun. Because it is a wave, it can be turned into a beam. The lengths of these waves are also just right to use them to get pictures at the atomic level. X-rays are the best option scientists have right now to capture these images.

However, there is a problem with x-rays. When they are really high powered (way more than ones that are used on people) they can destroy tiny samples. These x-rays are strong enough that they almost immediately destroy any small samples of tissue that the high-powered waves are shined on. Scientists managed to figure out that freezing the samples kept them safer, but the lasers were still destroying anything that made oxygen. Because of this, watching the process of photosynthesis seemed nearly impossible. But Fromme figured out how to fix this problem in the late 2000s.

Free Electron Laser and Crystals

Fromme created a research group to find a way to save her samples. Much of her work started with people telling her she couldn’t achieve her goals. This became a repeated occurrence in her life; people saying she couldn’t do something, before she would prove them wrong.

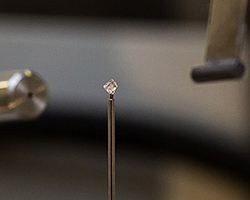

With a shortage of belief in the project and funding, it was an uphill struggle to fix the problem with the free electron laser. For five years, she and her research group worked with physicists to find a way to save their samples. They used new technology to make tiny crystals, which encased the sample. These crystals were named membrane protein crystals. The crystals diffract the destructive light that the laser shoots, and in doing so, they save the sample. The crystals can do this because the exposure is only a femtosecond (one quadrillionth of a second) long for each image.

So, the researchers were able to capture the images they need without destroying their samples. Now Fromme is working to make the entire system smaller (the current ones take up huge rooms) and to build her own laser at ASU. There are only ten free electron lasers in existence, so getting beam time is difficult for researchers. If the laser machines were smaller and less expensive to make, then more research could be done faster.

Fromme’s leaps with lasers didn’t end at studying photosynthesis. She has also applied these tools to research on cancer and medicine. Fromme had always wanted to work on helping people, but didn’t like the idea of doing research with lab animals. By using the free electron laser to research human cells she is able to help people without using animals. The free electron laser allowed Fromme to pursue all of her interests across plant and animal cells, something that not all scientists get to do.

Breaking Cell Boundaries was created in collaboration with The Biodesign Institute at ASU.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Leaf cells image by Des_Callaghan.

View Citation

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.