show/hide words to know

Arctic Food Webs

Across the expanse of sea ice, you see a polar bear, standing perfectly still, staring down. She looks surprisingly yellow, in contrast to the brilliant white snow and ice around her. While you may not think there are any other organisms nearby, there are.

This tiny Arctic cod uses antifreeze proteins in its blood to survive in literally freezing waters. Image by NOAA via Flickr.

Algae floats under the ice the polar bear stands on. Copepods, which look like tiny shrimp, dart around the water. They are eating algae and other tiny plants and animals. Arctic cod make their home here too, where food is plentiful and they can hide in pockets of water under ridged ice floes.

The polar bear is waiting for a seal that is hunting fish underwater to come up to the surface for air. The Arctic is full of life, and one way to think about all that life is in terms of who eats whom.

Trophic Levels

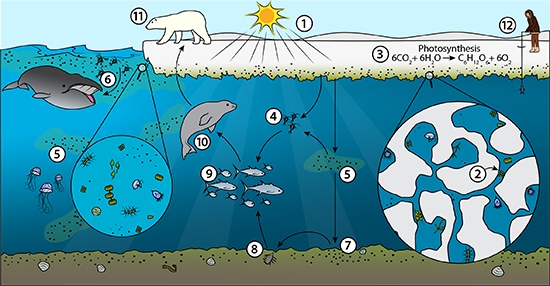

When one organism eats another, it moves stored energy around the food chain. The amount of energy that moves around can be represented by a pyramid. In the pyramid, the lowest level, or first trophic level, are the primary producers. These organisms, like plants and algae, turn the sun's energy into their own source of food. This process is called photosynthesis.

These microscopic shrimp, crabs, and other crustaceans are called "zooplankton." They are some of the Arctic's primary consumers. Image by NOAA via Flickr.

Next up in the pyramid, we have the primary consumers–they are the ones who eat the producers. Each consumer needs to eat a lot of producers. This means that the number of consumers who can survive depends on the number of producers in the area.

When these organisms are eating each other, the stored energy is being passed along the food web. Living is expensive in terms of energy. About 90% of the energy animals get from their food is used up to stay healthy and do daily activities. Only the remaining 10% or so can be used to grow. That 10% is what can be passed onto the next trophic level when an animal is eaten.

Below is a chart of trophic levels with Arctic animals:

| TROPHIC LEVEL | HOW IT GETS FOOD | ARCTIC EXAMPLE |

1st Trophic Level: Primary Producers | Photosynthesis | Ice algae, phytoplankton |

2nd Trophic Level Primary Consumers | Eats producers | Krill, clam, ice copepod |

3rd Trophic Level Secondary Consumers | Eats primary consumers and some producers | Arctic cod, squid |

4th Trophic Level Tertiary Consumers | Eats secondary consumers and some primary consumers | Ringed seal, beluga whale, polar bear |

Scavengers | Eats all levels of consumers that have recently died | Arctic fox |

Decomposers | Eats all levels of consumers and producers that have died | Bacteria |

You can also test your knowledge of the Arctic marine ecosystem with our game EcoChains: Arctic Futures.

Where the Walrus Fits

Even top predators like this polar bear can sometimes act as scavengers. Here is one eating part of a dead, beached whale. Image by C. Fallows and collaborators via Wikimedia Commons.

The trophic levels are a good rule of thumb, but it’s not always quite so simple. Most animals eat from a mix of the trophic levels, and some animals don’t fit nicely into one category at all. One such animal is the walrus.

Walrus are big animals, and not many other animals eat them. This would mean they’re a tertiary consumer. But we know that walrus like to eat clams, and clams are a primary consumer. Does this mean walrus are part of the third trophic level instead of the fourth? Not necessarily.

In a real ecosystem, most species don’t fit into perfectly defined boxes. Normally walruses eat things like clams, shrimp, crabs, soft corals, and sea cucumbers. But, when food is scarce, they are known to eat almost anything they can get, including fish like arctic cod.

Food Chains

Food chains show how energy moves through different groups of animals. Animals have to eat to survive and to get energy to do their daily activities. A food(link is external) chain only shows one direction of how energy is transferred. In nature, it is usually more complex as more than one animal might hunt a specific species.

Food Webs

When many food chains are linked together they create a food web. Most animals have many food sources and also have many predators. A food web shows these multiple pathways for energy to flow within an ecosystem. This helps give a more realistic view into what’s really happening in nature.

This section of Ask A Biologist is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1928235.

View Citation

A polar bear patiently waits by the edge of the ice, hoping to catch a seal to eat. Image by NASA via Flickr.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.