Milk - It Does a Baby's Immune System Good

show/hide words to know

What's in the Story?

Humans are mammals, a group that is named for their mammary glands. In most female mammals, mammary glands can produce milk for young. Image by honey-bee.

Why Study Breast Milk?

Breast milk has been described as “liquid gold” because it provides just the right balance of nutrients that babies need. But breast milk also has additional beneficial molecules that help protect babies from illness. Besides having a lower chance of catching an illness, breastfed babies that do get sick tend to recover more quickly than babies who are not breastfed.

In developing countries, where diseases are more prevalent, breastfeeding is especially important for keeping infants healthy. Thus, scientists are interested in learning exactly how breast milk is beneficial to infants, in a variety of different populations.

Breast Milk and Infant Immunity

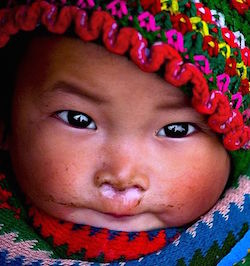

Lactoferrin and sIgA are found in mucus, which we are most familiar with from runny noses. Image by Bùi Linh Ngân from Hanoi, Vietnam.

Secretory Immunoglobulin A also hangs out around our mucus, stopping bacteria and viruses from sticking to our organs. It can also collect a bunch of bacteria and viruses into a big ball, which helps the body process and get rid of the bacteria and viruses.

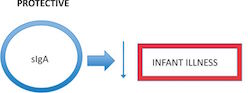

The researchers believe these immune molecules in mothers’ breastmilk may be playing two different roles:

1) In the protective role, the immune molecules are present in breast milk all of the time, so that illness can be prevented.

2) In the responsive role, the immune molecules are added to breast milk by the mothers’ body only in response to an illness in the infant.

The researchers hypothesized that any differences in the amount of lactoferrin and sIgA in breast milk would be associated with symptoms of illness in the infants. To test their idea, the researchers focused on the Qom/Toba people, a native population in Argentina. Many of the Qom people live in traditional conditions, such as in houses with dirt floors, and in communities with shared bathrooms, shared water sources, and outdoor cooking practices. Although the Qom have access to healthcare, their living conditions increase the chances of catching an illness relative to conditions in the United States or other more developed areas.

Connecting Breast Milk and Illness

Milk varies in its nutrition and concentration of immune molecules over time. Image by Azoreg.

Making Sense of Immunity in Milk

The researchers found that when lactoferrin was elevated in the breast milk, the infant was more likely to have been sick both before and after the milk sampling point. This suggests that lactoferrin may be playing a responsive role, which means the presence of the illness causes a rise in lactoferrin. On the other hand, the researchers found that high levels of sIgA in the mother’s breastmilk meant that their child was less likely to have been sick both before and after the study. This suggests that sIgA may have a protective role, which means that it may be present at all times to help prevent illness.

So we see, one way a mother can invest in her baby is to give it the immune molecules it needs to protect itself from illness. But rather than providing high levels of those molecules all the time, it looks like there may be a balance between what the baby needs and what the mother gives. The results of this study tell us that the mother’s body is always adding some healthy molecules to her breast milk, but when her child is sick, she is able to give an extra boost of immunity to try to help her baby fight illness.

Visit Digging Deeper to learn how to critique research papers using this article as an example.

EvMed Edits are sponsored by ASU's Center for Evolution and Medicine.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Painting of woman and child on menu thumnbnail by Alexey Venetsianov.

View Citation

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.