show/hide words to know

Say hi to Susan! She is a scientist working in a cancer lab. (Meet a real tissue engineering researcher at ASU here). Image by Marco-Alexis Chaira/ASU.

Tissue engineers in the lab

Susan is a scientist working in a cancer laboratory. She is studying the effects of a certain chemotherapeutic drug on breast cancer. She regularly grows human cancer cells for her experiments. So let's follow her around and observe all that she is doing today in the mammalian tissue culture lab. Keep your eyes open, as even the smallest detail may matter.

The contamination check

The first thing Susan does before entering the tissue culture room is to wash her hands thoroughly with soap. She knows that if bacteria and fungi can infect us, they can surely infect the cells in culture. So, she makes sure her hands are as sterile as possible. Once inside the tissue culture room, she takes two of her dishes containing cancer cells out of the incubator. She then places them under the microscope and quickly checks for any signs of contaminating bacteria or fungi. She doesn’t see any contamination, so she places her dishes in the laminar airflow (LAF) hood. This is where she will now do her tissue culture work.

Wait, what is a laminar airflow hood?

Tissue culture is done inside the laminar airflow (LAF) hood. The scientist is seated outside and puts only their hands inside the hood to perform the experiments. Image by Miles Smith.

The LAF hood is an enclosed bench where all cell culturing is done. LAF hoods maintain a continuous flow of air that passes through special filters. These keep out particles as small as 0.3 microns in size (dirt, dust, and many types of bacteria, fungi, and viruses).

Primary tissue culture

Of the two dishes, one holds a small bit of breast cancer tissue that Susan collected from surgery. Many of the cells from the tissue have started to move out of the tissue and attach to the bottom of the dish. Culturing of tissues or cells collected directly from an organism is known as primary tissue culture. Coming directly from the patient, this kind of tissue culture is perfect to study cancer. However, these cells have a limited life span. As our cells divide, the length of the ends of our chromosomes, called telomeres, slowly shortens. Once the telomeres reach a certain length, the cell stops dividing entirely and dies. So, even though these cells are great to work with, Susan can only work with them for a limited time span.

Cell lines

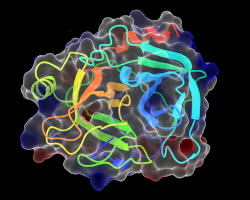

This is a 3D computer model of what trypsin enzymes look like. Trypsin helps scientists separate individual cells from each other and the dish. Image by 0fb1d8.

To solve this problem she has another dish with a breast cancer cell line. A cell line contains cells that can divide over long periods of time, sometimes even infinitely. These cells often come from aggressive cancers. Cells from such cancers divide uncontrollably. A cell line too starts off as a primary culture, where cells are collected directly from an organism. A small number of cells are then detached from this primary culture. Scientists use an enzyme called trypsin to detach the cells. Then, the cells are grown in another dish with fresh media.

After these cells divide and cover the entire area of the dish, a few cells are yet again taken from this dish and moved to another new dish. This process can be repeated as needed and is called subculturing or ‘passaging’. Repeated passaging results in a cell line.

Cryopreservation is used to store cells for long amounts of time. This is done by freezing them at super cold temperatures in liquid nitrogen. They are mixed in a solution which protects them from freezing damage. Image by the USDA.

Cell lines are commercially available. The one Susan is using is a breast cancer cell line made from an aggressive breast cancer. Because they are growing well, she detaches a few cells from the dish and freezes them at -80℃. This is called cryopreservation and helps store cells for years on end for future experiments.

Lastly, she puts a small amount of the chemotherapeutic drug that she is studying into both dishes and places them back in the incubator. The incubator provides the right conditions for the growth of the cells. All Susan has to do now is wait for her drug to do its job.

That’s a few minutes from the life of a tissue culture biologist for you. Let’s head out now, shall we? Also, good luck Susan!

Additional Images from Wikimedia Commons. Side image of scientist working under a laminar air flow hood by the US NIH.

View Citation

Cell cultures can easily be ruined if any dirt or germs touch them. This is why it is important to keep things incredibly clean when studying them.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.