show/hide words to know

Dairymaid: a woman who works in a dairy, where cows are kept, milk is collected, and certain milk products are made.

Mutate: to change; when the genes of an organism change.

The first vaccine

Njeri paces back and forth as she waits for the doctor to come out of her mother’s room. There are four siblings all together packed in the small living room waiting for news of their mother. Their mother has what the doctor called “smallpox,” but Njeri only knows that her mom is not feeling well and has spots all over her body. The doctor told them to leave her mother’s room and wait in the living room.

Smallpox is a deadly disease that causes raised bumps, often called lesions. It also interferes with our immune systems, which can ultimately lead to death. It is the only disease we have eradicated world wide thus far. Image by the CDC.

The doctor, a cousin of the family, now steps out of their mother’s room with a grim look on his eyes. He tells the children that their mother is very sick and may not survive. He asks that they go to their aunt’s house to avoid being contaminated themselves. Njeri is outraged and begins running toward the door to her mother’s room. The doctor catches her and carries her while escorting the others toward the door to take them to their aunt’s house. Being close to their mother would put them at risk of the deadly disease smallpox.

What is smallpox?

Smallpox was a dreaded disease that is estimated to have taken over 500 million lives. Luckily, in the 21st century, the risk of infection by the variola virus that causes smallpox is very small. Smallpox is now extinct thanks to worldwide use of the smallpox vaccine.

Smallpox had been infecting humans since at least the 3rd century BCE, but it is believed to have arisen in 10,000 BCE. The most easy-to-identify symptom was the skin rash which developed into raised bumps on the whole body. But smallpox could also cause high fever, headache, abdominal pain, vomiting, and organ failure. Smallpox often resulted in death.

Humans had been trying to find a cure for this disease long before the discovery of vaccines. It was known that those who survived smallpox were protected from being infected again. Those people were called upon to nurse others who got sick. Others also discovered that by rubbing fluid from smallpox sores into scratches in the skin or into the skin inside the nose, a healthy person could get a small infection and become immune. This process was called variolation (and sometimes inoculation). Variolation came with risks, however as 2-3% of variolated people would die from the infection. It was a risk worth taking as in 18th century Europe, 400,000 people were dying annually because of smallpox. But in 1796, that all changed.

Discovery of a smallpox vaccine

You see, smallpox was part of a whole group of viruses. Cows carried something similar, called cowpox. But cowpox was much less dangerous to humans than smallpox. It would create wounds (lesions) on the skin, but it wasn’t fatal. The story of vaccine discovery usually talks about dairymaids, and how many people believed that they were somehow protected against smallpox. But this is likely not the true story of how the smallpox vaccine was created.

A few different doctors in the late 1700s had taken note of how a recent infection with cowpox likely protected a patient from an infection with smallpox. However, cowpox infections could be more severe than an inoculation response to smallpox. In part for this reason, no one really considered treatment with cowpox (to prevent smallpox) as an improvement to their medical practices.

However, Edward Jenner, an English physician, didn't let go of this idea. He studied cowpox and found out that there were other diseases that were often mistaken for cowpox. He was also very observant and liked experimentation, habits he had learned from one of his previous mentors. In 1796, he finally got a good chance to do an experiment on the benefits of cowpox as protection from smallpox.

A young dairymaid, Sarah Nelms, had fresh lesions on her hands and arms from cowpox... there was a local outbreak happening at the time. Using fluid from her lesions, Jenner inoculated an 8-year-old boy with cowpox. A few months later, he inoculated him with smallpox and noted a much less severe response than normal. He responded as if he had already had cowpox or smallpox. Testing him again a few months later, the boy showed no response to smallpox.

Cowpox also created an intense infection with lesions all over the body. However, an inoculation with cowpox was less severe, and provided protection from smallpox. Image by the CDC.

Jenner’s experiment, plus a few repeated experiments, showed that an inoculation with cowpox (which prouduced a less severe response to cowpox) could indeed protect someone from smallpox. It also showed that cowpox could move from one person to another. The knowledge that you could protect against a lethal virus with an inoculation from a related, but less severe, virus was knowledge that would change the world.

Vaccine discovery continues

The discovery of the smallpox vaccine saved countless lives. It also influenced many scientists, including one named Louis Pasteur. Pasteur reasoned that a vaccine could be used to prevent other diseases, not just smallpox. You may have heard of Pasteur before, he came up with the germ theory. The germ theory basically states that many diseases are caused by microorganisms too small to see with an unaided eye.

Using this germ theory of disease, as well as Jenner’s vaccine discovery, Pasteur invented a vaccine for the disease chicken cholera in 1870, and one for rabies in 1885. The discovery of new vaccines grew like crazy beginning in the mid 1900’s. Thanks to Edward Jenner, we no longer have to fear smallpox, and can be protected from a wide range of different diseases by vaccination. The development of vaccines has also changed our modern world—new vaccines are still being developed today.

Move the circle along the timeline to see how smallpox cases changed over time. The timeline ends in 1977, as smallpox was eradicated from most of the world by then. Interactive image by ourworldindata.org.

Modern vaccines

In recent years, vaccines have been developed for different viruses such as human papilloma virus and SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Scientists are also currently researching how to create vaccines against herpesvirus, HIV, and Ebola, among other viruses. Each situation has unique challenges.

The research on a herpes (HSV) vaccine is difficult because HSV hides from the immune system in the nervous system. The nervous system is very important for the body’s function and any damage can be deadly. For this reason, the body can’t launch a full attack against viruses when they hide in the nervous system. The risk of accidently damaging something is too high. This makes it difficult for the immune system to fight the virus.

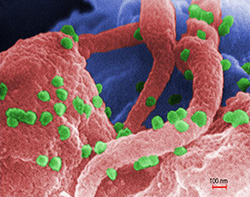

The HIV pandemic is still ongoing. Over 33 million people have died of AIDS worldwide. Here is a colorized microscope image showing small human immunodeficiency viruses attached to the outside of a comparatively large white blood cell. Image by the CDC.

An HIV vaccine is in the works as well, although this too is challenging. HIV changes (mutates) very rapidly, and because of this it has been difficult to make this vaccine. The goal of vaccines is to train the body to recognize certain germs. However, some germs are sneaky. They keep changing the way they look so it is hard to train the body to recognize them. Scientists don’t give up easily, though, and after a lot of work, some progress on an HIV vaccine has been achieved.

One vaccine that is currently in use, but not officially approved for widespread use in humans, is the Ebola vaccine. This vaccine has been used in at least one Ebola outbreak in Africa. The path toward the creation of a vaccine is one littered with obstacles, yet the goal is always to prevent disease.

Vaccines are one of the most important public health achievements of the 19th and 20th centuries. Which do you think is the next disease that will be cured by vaccination?

Boylston, A. (2013) The origins of vaccination: Myths and reality. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 106 (9): 351-354. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3758677

Riedel, S. (2005) Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings. 18 (1) 21–25.

SA Health. (2012) Smallpox - including symptoms, treatment and prevention. https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+...

Immunize for Good. New Vaccines on the Horizon. http://www.immunizeforgood.com/vaccines/new-vaccines-on-the-horizon

Public Health England. Historical vaccine development and introduction of vaccines in the UK. https://ewds.strath.ac.uk/historymedicine/View/Image/tabid/6227/articleT...

View Citation

Bibliographic details:

- Article: How were vaccines discovered?

- Author(s): Ian Vicino, Mary D. Pardhe, Karla Moeller

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: November 16, 2020

- Date accessed: January 9, 2025

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/vaccine-discovery

APA Style

Ian Vicino, Mary D. Pardhe, Karla Moeller. (2020, November 16). How were vaccines discovered?. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved January 9, 2025 from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/vaccine-discovery

Chicago Manual of Style

Ian Vicino, Mary D. Pardhe, Karla Moeller. "How were vaccines discovered?". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 16 November, 2020. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/vaccine-discovery

Ian Vicino, Mary D. Pardhe, Karla Moeller. "How were vaccines discovered?". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 16 Nov 2020. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. 9 Jan 2025. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/vaccine-discovery

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.